At the time of writing, Gallivantrix has 290 posts which average 4000 words each. That’s over a million words or two copies of War and Peace.

In 2024, I watched as my 10 year achievement flew by. It’s hard to mark a life of gradual change with anniversaries, but a decade is a good amount of time to take stock. I started the blog in May of 2014 while I was preparing to re-launch my international ESL teaching life by heading to Saudi Arabia that September. As I noticed both of those decade markers fly by in 2024, I thought to myself how nice it would be to sit down and quietly reflect on what the last 10 years has brought and how it has changed me. It is only now, staring down the barrel of the New Year that I finally feel like a quiet sit-down is possible. Still, better late than never.

A Life Dedicated to Travel

In the last 10 years I have lived and worked in 4 foreign countries, and visited an additional 27. That’s more than ¾ of the international travel I’ve done in my lifetime so far and nearly all of the travel I have done as an adult. But what does it mean to live a life that nomadically?

One of the big things that I encounter when I tell people how I live is envy. I have no illusions about how amazing the experiences of my life have been, nor do I think I live in a way that is accessible to everyone. It can be a bit strange to remind people that I’m not rich, and in fact, have spent chunks of my life being poor, eating from food-banks (charities), and relying on friends for a roof over my head. And, no, I didn’t win the lottery or get an inheritance. Luck, circumstances, and the support of others have played a big role, but also I made a conscious choice to prioritize travel over almost everything else in my life, and then I worked very hard to make that happen.

I found a career that allowed me to work in a variety of countries. I took extra education to gain the necessary credentials. I took terrible jobs to build experience. I reduced my life’s possessions to what would fit in 2 large suitcases and a carry-on. I had no home, no car, no bed, no books, no dishes, no spouse, no children, no pets, no musical instruments, no garden, I gave all my art away, and my sister is keeping the few family heirlooms we treasure. I ate cheaply, used public transit, and wore free, thrifted, or clearance bin clothes. I bought second-hand phones and cheap laptops and used them until they died, relying on my office computer for any big projects. I only got a portable video game system during COVID because I couldn’t go anywhere.

I don’t feel like I’m missing out on these things because I don’t have them, but I think it’s helpful to remember that no one actually “has it all”. The people who envy me usually have stable, local jobs, a lease or a mortgage, a car (and payments), kids and pets, a multi-seasonal wardrobe, hobbies and crafts, new phones and complex computer set-ups, and a lifetime of memories in the form of stuff that has to have a place to exist. They can’t afford all of those things AND prolific travel, but neither can I. I didn’t make that choice all in one go, either. It took years of gradual change to reach a point where I have a 2-suitcase life. I had plenty of chances to change my mind and back out, but I *like* my life. I just want others to understand it isn’t a traditional life + travel, it is a life purpose-built for travel.

From the Inside

10 years is a long time no matter what lifestyle you have, and I hope that everyone grows and changes in that amount of time. It is a well-studied phenomenon that travel has a big impact on the human brain, and sustained travel with its joys, challenges, and culture shocks has forced me to look more closely at myself and my place in the world.

Although therapy didn’t take a starring role in the blog until COVID-times, it’s been an on and off part of my personal journey for a while. In the 2 years leading up to the launch of Gallivantrix and my international life, I dedicated a lot of my free time to researching and practicing positive psychology. TED has a wonderful series of talks on the subject and several practical resources that I still recommend to people like Superbetter and AuthenticHappiness.

I believe it was a direct result of this work that I was able to embark on the journey, but it did more than give me the strength to adventure. From 2015-2019, I gradually changed the way I approached interactions with others. Some of this work resulted in stronger, healthier relationships and some resulted in the end of years-long ties. The people who remain in my life are strong communicators & loyal friends. Those who left were, for the most part, not “bad people”, they simply had their own struggles with trauma and healing that left us incompatible. Perhaps the hardest of all of these was with my mother.

From 2020-2022 I dove back into the world of mental and emotional health, this time with a focus on childhood experiences and generational trauma. You can read through my book list in the archives if you’re interested. Even though I made good progress using these tools, the circumstances of the pandemic meant that by the end of 2021 I needed to make plans to leave Korea and get out in the world around other people in order to keep improving.

Bouncing off to Senegal after years of isolation may have been a bit like trying to ski black diamond right after recovering from a compound fracture. It hit me hard, and you can see most of it in the essays I wrote during that time. I will be forever grateful for the experience, for what I learned and how it changed me, but it was not the joyful return to global travel that I had been craving. It took me 9 more months of trying various things and eventually moving to France to finally find what I was looking for in myself that I thought I had lost in 2020.

10 years of international living, a global pandemic, and a deep commitment to emotional healing later, and I am now a much more emotionally mature person than I was in the past, capable of identifying and sitting with my feelings to understand what is reasonable, and what is reactionary. I am able to approach conflict resolution with an eye toward responsibility and solution instead of blame. I know my limits mentally and physically and I plan my life, work and travel in such a way as to protect the hard limits while pushing soft ones. I want to make the world around me a better place, and while I’m ok doing that one person at a time, I’m also interested in how I might do more. I have learned so much about the world and the human race, that I will never be able to look at it without that knowledge seeping in. At some times that is beautiful, and at others it is profoundly painful. I have flaws, just like every human, but I am learning to love myself, and to extend grace and compassion inward and outward for flawed humans everywhere. I don’t want to look away.

Accommodating My Needs

Whether you want to call it chronic illness, invisible disability or anything else, there is a growing awareness of this category of health issues that limit what people can do without making us unable to work, travel, and live independently. I received my first couple diagnoses as a late-teen/young adult, so it isn’t new to me, but as I age, not only does the list get longer, my ability to simply push through my limits is sharply diminishing.

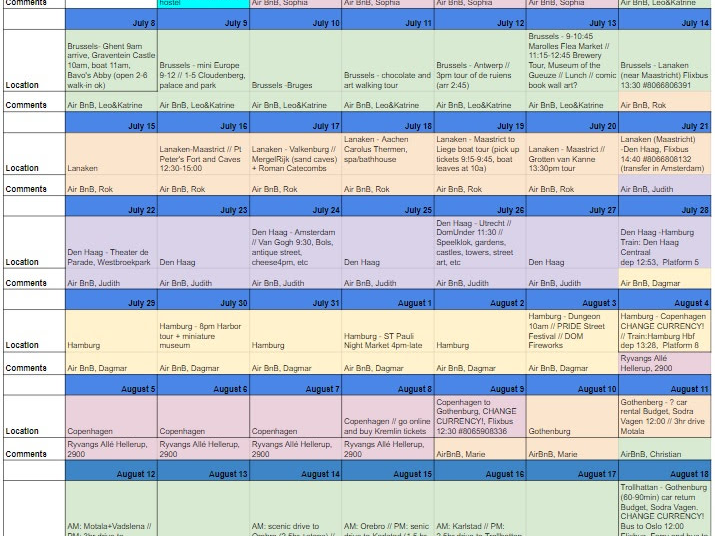

Back in 2018, I had a real “come to Jesus” moment during a long summer holiday backpacking across Europe. It made me start rethinking my priorities and what tools I could use to make the most of my travels without destroying my physical and mental health in the process. Over the next three trips, and the pandemic induced therapy-work, I slowly built not only a list of practical tools to make travel easier and more enjoyable, but also the ability to accept my limitations. The second one means I don’t get so tempted to do things which will result in burnout later on, and I get to enjoy things I am able to do without dwelling on regrets, missed opportunities, or generally hating my body.

I am more likely to book larger seats on long haul flights because I know the difference it makes in my recovery time and pain levels. I always check the accessibility options for places I will stay, including distance from transit, number of required stairs, and how far the toilet is from the bed. I take extra time when walking everywhere, usually planning at least double the Google Maps estimate. I carry snacks, meds, and water everywhere. I keep a little extra in the budget for when I need to catch a taxi or ride-share because the walk/transit is too much. I accept that hot weather means I’ll need extra rest and extra painkillers, and I must plan to do very few things.

That last one continues to boggle the mind. Spending spring in France, I was able to walk longer distances and do things for hours, even spending 12+ hours a day walking around some places! I’m never going to be up for a 5k run, but when the weather is mild-cold, I have so much more energy and mental focus and so much less pain. It has become important for me to keep notes when I am in different climates because it’s easy to forget how dramatically the heat affects me, and I need to be able to reference daily and weekly records of my experiences to hold onto the fact that it’s real and not a trick of memory.

Even knowing this, I still choose to go to hot places sometimes, like India… in August. But I made sure to always keep water and NSAIDs on hand, to walk very slowly, use a sun-shielding umbrella, and crank the AC in the car and the hotels. I was exhausted by the end of it, but I got to see some very amazing cultural and historical sites. I also went to Taiwan for 3 months starting at the tail end of August, knowing that the weather would be too hot until October. For the first 5 weeks, I did almost nothing besides go to class and get food. I knew heading into Taiwan that I would not be able to do a bunch of touristy things, but I still wanted the language study and cultural experience, so it was worth it.

Accepting my limits doesn’t keep me from going places, but it changes the way I go and what I expect to get out of it. I may not get as much out of my trip to India or Taiwan as a more healthy and fit person, but I definitely get more out of it than someone who never goes at all.

From the Outside

When I started the blog, I harkened back to the early days of social networking (Live Journal, My Space, and even bulletin boards!) where everyone who was online in those days was producing what we now call “content”. I know I sound like a get-off-my-lawn antique (and I am GenX), but objectively, it’s not just me that’s changed in the last decade. The internet / blog-o-sphere and the world at large have also undergone some dramatic makeovers in that time, too.

Demographics

It’s always hard to compare the present to memories of childhood, so I can’t say how much of what I recall about the travel I did with my family as a child is accurate, but one thing I think is objectively measurable is just the sheer number of people flooding popular travel destinations.

When we lived near the beautiful white sand beaches of Panama City, Florida, my mom and I joked about buying shirts that said, “I’m not a tourist, I live here.” because we felt like we could hardly go near a beach without being accosted by cheap seashell trinkets (made overseas) and green key-lime pie (it’s supposed to be yellow!). Perhaps because of this formative childhood experience, I have never enjoyed a tourist trap even though I have not always been able to avoid them. Yet, when I lived in Florida, the population of the US was 107 million fewer people than it is today. Not all of them visit Floridian beaches, but it stands to reason that the population rise alone will result in more humans per beach.

This NYT headline said in 1984, 27 million Americans travelled abroad, a new record at the time. By 2014 that number was 68 million, and by 2023 it was 98.5 million. Data on 2024 isn’t out yet, but I would bet it breaks 100 million. And that’s just Americans!

The global population has risen by almost a billion (that’s B) in the last decade, and more and more of them are living higher wage, higher quality lives which include international travel. Over 1.1 billion tourists (15% of the global population) travelled internationally in 2014, in 2019 (just before the pandemic) it rose to 1.5 billion (roughly 19-20% of the global population). Obviously, the pandemic saw a lapse in travel, but most statistical analyses agree that in 2024, international travel levels caught up with and then exceeded 2019 levels.

Also, there’s more people living in most of the popular locations. Only a few countries have been experiencing declining populations. Meanwhile, swift urban development and technological advances mean that a smaller percentage of people are living a rural/agricultural life, choosing instead to flock to cities and suburbs for better schools and higher paying jobs. In many places, migrant workers who come in to do things like drive taxis, work in kitchens, clean homes, and do construction do not show up on official statistics of urban populations, yet they certainly contribute to the body count.

When I arrived in Senegal, many people told me that the city had nearly doubled in size since the start of the pandemic, and that the cost of living was skyrocketing as migrant labor from the villages flooded in. Although official statistics show about a 3% yearly rise in population for that city, that is still much faster than the infrastructure can keep up with. Senegalese citizens and immigrants from less stable West African countries want to live in the city because they can earn more money to send home to their families. The flood of people coming in has resulted in overcrowding, lack of adequate sanitation, lack of housing, lack of food, and lack of employment.

Dakar isn’t a hotspot for tourism, but many developing countries that rely on tourist dollars are experiencing a similar trend, meaning more locals are in the cities we travel to and more of them are struggling to get by. My foray to Zanzibar in East Africa highlighted this most dramatically where I would walk through a neighborhood with no running water to reach the high end resort hotels on the beachfront. As hard as it might be to live in a developing country and see first world lives on TV and the internet, how much harder must it be to see them across the street when you must carry water from the well and dig a hole for a toilet?

Among the expat communities, people who live and work abroad, not just traveling for fun, we have anecdotally noticed an upturn in the tendency to be treated as a “walking ATM”. The rise in the number of locals living in cities but struggling financially has led to a (totally understandable) level of desperation in the competition for foreign dollars that hasn’t always existed. And don’t get me wrong, I feel an enormous amount of compassion for those less fortunate than I who have not had the chances and support or even the citizenship that give me my advantages. However, I cannot singlehandedly change the fortunes of a developing economy with my few thousand dollars.

Then, when I come back to the US, I am shocked at prices and poverty here, too. 100 million of us may be able to travel internationally this year, but how many of those scrimped and saved to do so? How many are using airline miles they earned buying groceries and gas? How many only go once a decade or once in a lifetime? How many are taking on debt to do it? And of the remaining 235 million, how many are food insecure (47 million), how many are one paycheck away from homelessness (200 million). People shouldn’t travel if they can’t afford it. Please, do not travel on credit! But regardless of how we pay for it, most people can’t afford to go over a carefully planned budget while on holiday.

I want to spend my money on local small businesses when I travel, but it isn’t fair to be treated like a bottomless money pit because we were born in affluent countries. What’s more, it makes for a very unpleasant experience which will only damage the future of their tourist economy. I work hard to avoid these kinds of situations, and have developed tactics over time to deter scammers and hawkers, but it’s exhausting and demoralizing to be walking around a beautiful historical and/or sacred monument only to have to fend off junk-sellers every 5 ft. Many take “no thank you” and move on, but others will follow you around telling sad stories about their kids to try and guilt you into buying some cheap trinket you don’t want.

This experience isn’t new in and of itself, as I recall having had it in China back in 2005, but it feels like the number of such “sellers” and their persistence, willingness to invade personal space, and leverage emotional manipulation has dramatically increased. I think it was one of the big reasons Senegal was so hard for me, as well as the main reason why in places like India and Egypt, I opted to hire local drivers and guides who I can budget a gratuity for in advance, and expect them to act in part as a barrier to the other hands being held out for cash.

The upshot of all of this population growth, demographic change, and economic inequity is that many places are more crowded and fighting harder to extract every penny from the visitors that they can. There are still places in the world that do not have this problem, or at least do not have it in excess, but I feel like it’s much harder now to plan a trip that avoids them, especially if you have any bucket list items that include major historical sites, world-class museums, or unique natural wonders. Maybe it’s easy for me to say because I’ve already gotten to visit quite a few of these, but now when I give travel advice, I tell people to focus on small local experiences rather than grand bucket list ones since you’ll be more likely to have the space and peace to enjoy it.

Going Viral

In addition to the population and economy, there’s one more very large factor that’s changing the face of travel and travel-blogging: the social media revolution. My 5 week stay in Tours France was relaxing, idyllic, and felt almost nothing like tourism at all, but when I left Tours and went on my color-coded-spreadsheet trip of tourist highlights including Disney, Lyon, Marseille, and all the big bucket list spots in Paris I had somehow never gotten around to like the Louvre and Versailles. Although almost every place I went was new to me, the experiences of being a tourist all seemed eerily familiar.

Authors and researchers like Jonathan Haidt have been studying the changes in social media over the last 10-15 years, and there are some fairly strong conclusions about the manner in which content is created and consumed. Other old-fashioned travel bloggers like me who want to share personal content over rubber-stamped listicles are also expressing frustration.

As social media drives attention to ever more similar short-form bucket lists and glam photos, tourist attractions have also started to become homogenized. This isn’t all bad, nor is it fully ubiquitous. I have written before about the fact that cathedrals in western Europe are all kinda the same in the way that roses are all kinda the same, and I still like them both every time. Huge enough attractions like Disney and Versailles don’t need to change too much to keep attracting visitors, and they will always be tourist processing machines filled with photo-happy crowds and overpriced souvenirs. Yet, everything in between seems to be riding a post-Instagram, post-COVID wave of striving to provide travellers with photo-ready experiences that exactly mimic what they have already seen online. Stand in this line to get the perfect photo, order this dish at the restaurant, look for this “hidden gem” that’s now overrun with tourists, and always post your best photos!

I have been going to Angelina’s in Paris since 2015 (that makes it sound like I go a lot. I do go at least once every time I visit, but it’s only like 6-7 times total) and yet sometime between 2019 and 2024 it got internet famous, and for the first time ever, when I went this year, there was a LINE out the door and they were no longer accepting reservations. My patience was rewarded in the end, and when I went back a few weeks later at a better time, there was no line at all. Despite Angelina’s appearing to have handled their newfound fame well, many local restaurants that receive viral treatment do not.

Internet fame can send tourists in droves to small businesses that are unprepared for the volume of new customers which ends up leading to disappointing experiences and bad reviews. Some businesses overextend themselves financially trying to keep up, only to be left with debt when the viral spotlight turns elsewhere. Very few small-scale restaurants survive viral fame, and even fewer benefit from it. Additionally, the desire to have a replica of the online experience leads to long lines at one location while those around it languish. This is bad for both local businesses and for the tourists themselves. The joy of a hidden gem or hole in the wall is that it is unique, different, likely thriving off of local and seasonal ingredients meaning that the dining experience is different from day to day. Meanwhile, viral sensation seekers want to experience what they have seen online and nothing else.

Jerusalem Demas famously wrote, “Tourists are like bees. I don’t want a bunch of them circling around me, but I also don’t want them to disappear.” Developing countries are not the only ones that are both economically dependent on, and simultaneously damaged by increasing tourism. Many large cities in affluent developed nations are experiencing an overdose of tourists that is causing chaos and unhappiness among the locals. This Forbes article goes into more detail of the struggle between reliance on tourism for economic success and the damage that over-tourism brings.

Viral fame hasn’t just damaged food experiences, but also art, music, and nature. One beautiful Mediterranean beach may be edge to edge bodies while a few villages over, a pristine beach boasts only a few locals. The government of the Philippines had to shut down some extremely popular tourist beaches because the sheer number of tourists was damaging the environment, yet there are hundreds of practically empty beaches around the Philippines that no one is going to. Is it because they don’t know about them or because they want to recreate that experience they saw online?

Imitate and Recreate

When “influencer” first became a job, they would try to use clout or ad space to get free meals and accommodations. A very small number of extremely successful ones still can, but remember a billion+ people are traveling every year, so an influencer with a million followers is only 0.1% of the potential market, and most of their followers aren’t actually going to travel, because travel lifestyle influencers are largely aspirational.

Now the issue is less influencers trying to get free stuff and more that a small number of tourists with influencer dreams have their hearts set on recreating a viral photo or video on location. Surveys and polls vary a bit, but generally speaking somewhere between 50-80% of Gen Z consider influencer a desirable and realistic career option, with more than 40% of adults overall feeling the same.

As a result of this, you get people doing choreographed dances in the middle of a UNESCO World Heritage site, or self-employed ‘models’ posing over and over in front of the thing that literally every other tourist there wants a photo of. This has gotten so bad that in many places, the government or local businesses have posted signs banning tripods and costume changes.

I am not criticizing dancing nor taking photos. Normal polite people usually spend a few minutes taking photos, arranging poses, and checking to make sure no one was making funny faces before moving on. On the rare occasion I indulge in a selfie, I tend to take a handful before I get one I don’t hate. I think it’s fair to want to look your best in your photos. But these people will stay for 30 minutes to an hour, taking pose after pose or restarting their dance 17 times, all while blocking everyone else from being able to take photos of the site. Tourists are often on a tight schedule, and will end up missing out on their photo ops for their own memories because a wanna-be influencer can’t share.

Even when they aren’t taking photos, they will often sit or stand in desirable photo-op spots to scroll their phones instead of moving off to the side to allow others a chance. And again, I’m not criticizing wanting to check your phone while at a famous landmark or museum or whatever. They might want to make sure photos turned out; they might be checking their itinerary for the day; they might be reading about the site they are visiting to learn more; they might be trying to contact their group; they might even just be scrolling because it’s so crowded and overwhelming that they need a break. All of these are fine and valid reasons to be on your phone. None of them are reasons to block the view while you do it.

AI photo editing has made it easier to cut out unwanted hordes of tourists, but it can only do so much. Plus, my photos are primarily a gateway to my memory. I can wait for the perfect shot or edit out a stray person in the background, but if I look at the photo and remember the obnoxious influencers and pushy junk-sellers more than I remember the awe and beauty of the place I came to see, then what am I even doing?

What Am I Even Doing?

In 2014 when I started this website, there were (according to Google) hundreds of thousands of travel bloggers across several platforms. Now in 2024, those same estimates place the number of travel bloggers in the millions. Far and away the vast majority of them are just in it for the money. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to a bit of extra cash to support an already expensive hobby, but the current monetization model of social media pays for eyes, for attention, for engagement, and so using keywords and creating short 1 min or less content allows social media influencers to maximize money while minimizing effort. Millions of travel content creators exist, yet the format for a travel blog has been trimmed down to those few most monetizable models on platforms like Instagram and TikTok, meaning everything is starting to look the same while containing less and less original or unique information.

I have never thought of Gallivantrix as something to monetize, no matter how many times well-meaning people suggest that I turn this hobby into a side hustle. I hoped my blog would primarily serve as a way to connect with my loved ones while I was abroad, give people a deeper perspective of the world, and maybe add a soupçon of helping other travelers. 5 years ago when I checked in about my motivations for writing, I stood by my long-form and intermittent style and I am still drawn to long form essays with no particular schedule, but the content of my writing is changing.

I have always been an essay writer, tending mainly towards narrative essays. I used to call my writing style “narrative nonfiction”. Sometimes, I write descriptively, giving detailed accounts of what an experience is like, to paint a picture that my readers can imagine. Sometimes I involve research and write more informatively to talk about the history or broader context of an experience. Since COVID, my writing has taken a more personal bent, with liberal doses of expository and reflective writing.

Writing narrative essays about my experiences not only allows me to share my adventures, it gives me good motivation to go out and do things and to live mindfully while experiencing those things. By setting myself up to notice things “for the blog”, I’m more likely to have a deeper and richer experience and remain mindfully present. Later, writing the memory allows me to review all the photos and relive the experience vividly in order to record it. I may not want to do this for every single place I visit, but it’s a great tool to have in the box.

During my France holiday, I wrote narratively about Tours, and I meant to do the same for the other places I visited, but over and over I came up against the idea that I could not say anything that was not already said both more succinctly and more informatively.

It seems now when I’m travelling in places that are inevitably viral, I no longer have any interest in publicizing my journey. I still take photos and share them with my friends, and I write little highlights for myself, things that in the past would be the notes I used to write blog posts from later, but I don’t have any interest in spending hours creating content that a million other people have already created. I found that when I am already in a good headspace mentally and emotionally, I am able to be mindful and present in the experience. It isn’t necessary to try to find ways to make yet another blog about Disney, I could just enjoy it.

When I went to South Asia, I was surprised and inspired by Sri Lanka in part because since the civil war and the earthquake, not a lot of people have focused on tourism and travel there. I never have time to write while travelling, so I tucked it away for later, only to be confronted with the contrasting experience of India, and capping off my South Asian odyssey with a visit to a third wildly different environment in Nepal.

I knew I didn’t want to write a bunch of blogs about sightseeing and history at places which have been endlessly blogged about, but I started to think about how I would like to write about South Asia. Nestled in between my May and September decade markers, the trip made me think about who I want to be in my next decade as Gallivantrix. I thought about the essays I wrote in the pandemic about deep emotional issues, those that I wrote while in Senegal about the social, political and economic impacts of colonialism and white supremacy, and about the essay I wrote in France about finding joy in the everyday. I want to combine my experiences as an expat and tourist with what I have learned about the world, historically, politically, and economically, and how the countries I visit fit within that broader understanding. I don’t intend to fully discard narrative or informative writing, but I want to embrace the personal and the reflective.

Is anyone even interested in reading something like that? Wouldn’t it do better as a podcast? A video-essay? Is my approach too old-fashioned, too long, too nuanced, or just not cute enough? Eeehhhh. There’s millions of travel bloggers out there, but I don’t need an audience of millions. I hope there are a few people in the world who will read and think and share those thoughts with others. In the end, I write what I most need to say in order to process my experiences and ideas in a flow of words that may be only for the void.

If you happen to be here in the void with me, Happy New Year.