This is not a “fun” story of joyous tourism exploits and happy expat life. I had a lot of fun in Zanzibar, and I even had quite a few memorable good times in Senegal, even if most of them never made it into the blog. However, living and traveling in both places, I confronted some things that were hard to see, hear, think about, and know. I am personally both deeply pained and extremely grateful to have been smacked so far out of my comfort zone that it took me most of the year to process through denial, anger, sadness, and bargaining to reach a place of fragile acceptance. I travel to experience and learn, not just to have a good time. Though it is difficult, these aspects of a globetrotting life are just as treasured as my fun memories because they help me to understand the complex world we are all a part of in and to be a more compassionate human being to those around me.

Note*: Thieboudienne (pronounced chebu-djen) is the national dish of Senegal featuring fish and rice. My title is therefore a play on Douglas Adams’ book with a similar name: “So Long and Thanks for All the Fish”, also known as what the dolphins said in their final message to humans at the end the Earth.

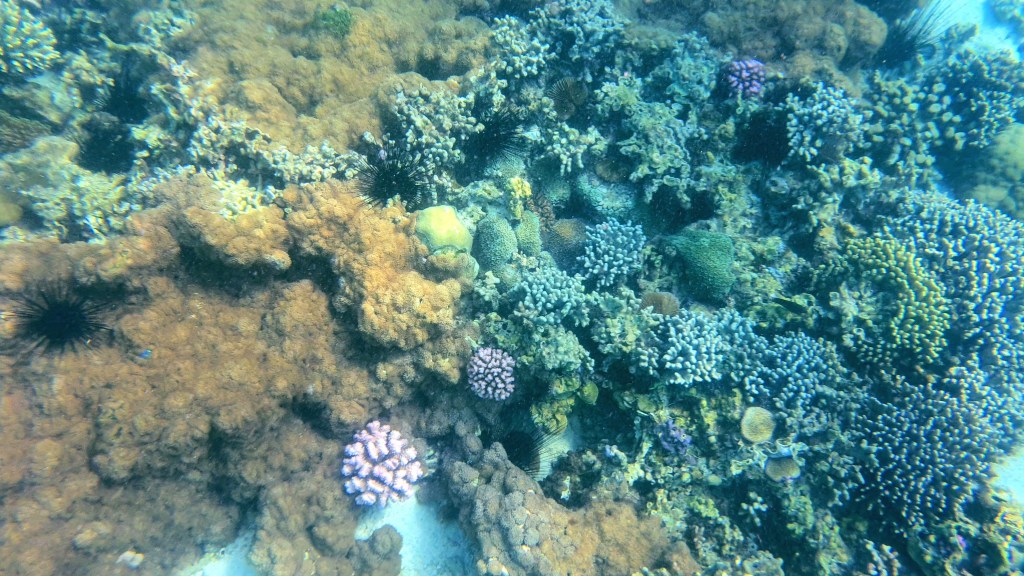

The Stone Town Slave Museum

Just as every historical tour in Europe has a section about WW2, every historical tour in Africa has a section about the slave trade. Zanzibar was the center of the East African slave trade, where slavers from the interior brought their captives by forced marches overland and a short boat trip to the slave market in Stone Town. The city where I live (Dakar, Senegal) has a similar historical site on Gorée Island, which is the center of the West African slave trade, and has a similar legacy of gathering slaves from the interior in one place to board on ships. Slaves went not only to the new world to work sugar, tobacco, and cotton plantations, but also to the Arabic world. These sites which commemorate the worst of humanity are not fun tourist attractions, but they are worth visiting because they instill a sense of reality that no amount of textbooks and documentary films can convey. You are standing where the people stood, both the boot and the neck. The blood is soaked into the earth and stones.

In the case of the Zanzibari slave trade, there existed a type of slavery before the growth of new world plantations exploded demand for free labor. Intertribal slavery between African (and indeed First Nations people in many parts of the world) was not uncommon, but it was a much smaller part of the economy. Prisoners of war were taken as slaves and although some were treated badly, some were integrated into the new tribe over a period of years. No version of slavery is “nice”, but I think it’s relevant to acknowledge how different slavery was in Africa before the foreigners got involved. Not only my guide, but a few other locals I spoke to there tried to excuse the West saying we wouldn’t have bought slaves if Africans weren’t selling them, and this is a level of internalized shame that I’m not ok with.

The increased demand for millions more slaves to serve in the Arabic peninsula and the new world colonies changed the entire dynamic of slavery and the economy of many places in Africa. The slaves that had previously been taken as prisoners of tribal skirmishes weren’t enough to meet the export demand and so a new industry emerged: to wage wars for the sole purpose of taking slaves. Government leaders also captured and sold their own people when they couldn’t get enough from “enemy” tribes. Slaves were forced on long marches with little to no food or water, and those who fell sick were left to die.

By contrast, the free people in Zanzibar prospered by collecting fees from the inland slavers as well as the foreign traders for every slave sold in their markets. When the West abolished slavery, the leaders in Zanzibar didn’t want to stop because it was too lucrative, even without the Euro-American market! The modern attitudes of hakuna matata and pole pole (no worries, and take it slow) on the island are likely a direct result of the fact that for centuries the islanders had to do very little work for the passive income of slave taxes to make them comfortable. Although they no longer sell anyone directly into slavery, the local governments in many places in Africa continue to exploit their own people in extreme ways in order to preserve the legacy of easy money their ancestors had in the slave trade days.

The slave museum in Stone Town tells not only of the horrors of slavery, but also of Livingstone’s mission of abolition. While some in the West may see Livingstone as an embodiment of the “white man’s burden”, many in Africa still praise his abolitionist efforts. Although it was the British government and navy that did most of the work of stamping out the slave trade, Livingstone’s published accounts of the atrocities of the slave trade in Africa helped spread discontent with the continuation of the practice. In American education, the end of slavery is often taught as something that just happened one day upon the signing of the Emancipation Declaration. Few white Americans know the history of the holiday Juneteenth (June 19th) celebrating the day the last group of confederate forces in Texas were finally uprooted, freeing the remaining slaves almost 2 1/2 years later. Even fewer know that the last slaves weren’t actually freed until 6 months after that with the 13th amendment. Almost no one I talk to knows that the 13th amendment didn’t end slavery for all – it’s still legal as a form of punishment for criminals in the United States.

The museum in Stone Town makes no bones about the lengthy process of eliminating slavery and the challenges newly freed slaves faced with no homes, no money, no family ties, and nowhere to go. Even after the Sultan finally caved to the pressure to stop the practice of selling slaves, he didn’t banish the owning of slaves for some time after. The women were the last to be freed because owners tried to claim them as wives rather than slaves, and the difference wasn’t easy to spot. Freed slaves were taken to “apprentice” at plantations where their lives were little different from they had been before; the only difference being their backbreaking labor was rewarded with meager wages and their food and housing came at a price. Freed children were sent to Christian missionary schools which molded them into “good” colonial citizens and converts. Slowly, the freed slaves were able to use their meager wages to move away from the plantations and missions, some to uncultivated land and others to the city for urban work. The legacy of the slave trade is long lasting for Africans everywhere, and museums like this help us understand not only our history, but our present — and hopefully help us to shape a better future.

The abolishment of slavery in the 19th century only made slavery illegal, yet it still continues to this day. Slavery exists in every country of the world and has dramatically increased in the 21st century. There are more slaves today than were seized during the entire African slave trade. While some countries have larger numbers than others, it is an issue that affects all of us.

Modern day slavery is defined as a relationship in which one person is controlled and exploited by another, usually by the use or threat of violence, for the purpose of profit, sex, servitude or the thrill of domination-deprived of free will, restricted in movement and paid nothing beyond subsistence. A slave may be kidnapped, captured, tricked or born into slavery.

Modern slavery is a hidden crime The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates the illicit profits of forced labor to be $US150 billion a year. From the Thai fisherman trawling fishmeal, to the Congolese boy mining diamonds, from the Uzbeki child picking cotton, to the Indian girl stitching footballs, from the women who sew dresses, to the cocoa pod pickers, their forced labor is what we consume. Modern slavery is big business.

TYPES OF MODERN DAY SLAVERY

BONDED LABOUR

Workers who have received or are tricked into taking a loan and are unable to leave until their debt is repaid. Often times, children of bonded laborers must continue to work off the debts, leading to generations of enslaved families. It is the most common type of slavery today.FORCED LABOUR

Any work or services which people are forced to do against their will under the threat of some form of punishment. Almost all slavery practices, including trafficking in people and bonded labor, contain some element of forced labor.CHILD SLAVERY

Children who are used by others for profit. For example in forced marriage, prostitution pornography begging petty theft, drug tracing, labour, armed fighting or wives’ for soldiers. Usually, child slavery is accompanied with violence, abuse and threats.EARLY AND FORCED MARRIAGE

Women and girls entering marriage without choice, forced to live a life of servitude often accompanied by physical violence and with no realistic choice of leaving the marriage.DESCENT-BASED SLAVERY

The legal ownership of a person by another person or state, including the legal right to buy and sell them as any common object.Products made by modern day slaves flow into the global supply chain and eventually into our homes leaving most of us unaware of our contribution in supporting it.

From the Slave Museum, Stone Town Zanzibar

A Talk With A Zanzibari Guide

My guide around Stone Town was a young man of mixed Arab and Swahili heritage (his mother is Arabic and his father Swahili) and I think had a unique perspective on Zanzibari culture as a result of living with one foot in two worlds while belonging to neither. When we reached the church at the slave museum, we sat down for a break from all the walking in 33C/UV11 weather and he opened up to me about his life. As with any personal account, I know that it’s his perspective and opinion, and not an objective truth, but I found it to be a fascinating conversation, and I’d like to share some of what he told me.

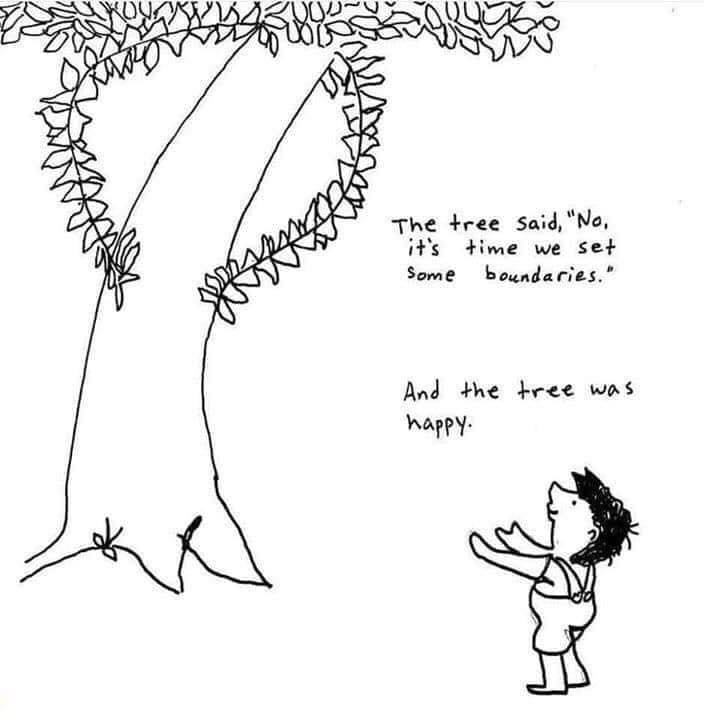

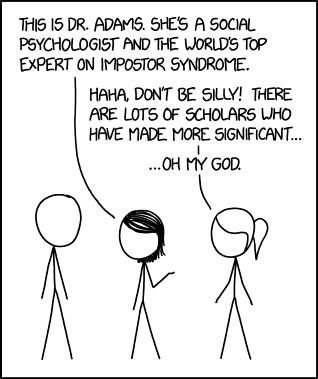

What he described to me was a life of codependency. I know Americans are extremely independent, and I’ve seen how extended family structures can bind young people in other countries often making them feel like they have no choice in what they study or who they marry. Yet what my guide explained to me of the family networks here, it is not only impossible to survive outside of one, the parents (especially fathers) can be very harsh, and abuse is normal. He shared his opinion that children need to have things explained to them because just hitting them makes them live in fear, so I hope that when he has his own children he will practice this. His parents are less bound by their own families. Both families disapproved of the mixed marriage, so they had to go it more independently. He feels very lucky to not be bound by the familial codependence he sees his peers trapped in.

Women have little freedom. He said most men have 2 wives (though they are allowed up to 4) because the first wife will be who his parents want him to marry, and the second will be who he wants to marry, which seems critically unfair to everyone involved. Women are encouraged to stay at home. Though young girls here are in school, many don’t pursue a degree after high school or have any desire to work outside the home. Parents pressure young women to prepare for marriage and think men will not want a woman who works (or possibly that a woman who earns her own money will put up with less BS from a husband?) My guide told me that many young women watch romantic dramas from around the world and get the impression that marriage will be a better life than getting a job, and are later very disappointed that it’s not true. My guide said hopes to find a wife who wants to work, not because they need more money, but because she wants something for herself.

Men are also trapped into a life decided by others. They must go into the career their fathers choose, marry the woman their parents select, and spend their salary to support their own parents, their wives’ parents, their wives, and their children, meaning a single salary supports up to 7 adults and possibly more than 7 children. Zanzibar is even more economically challenging because people from the mainland come over and do jobs for dirt cheap (140$ a month!). Mainlanders can send home 20$ and it goes a long way to support the family living there, while families that live in Zanzibar need 350$ or more a month just to scrape by. A gift of 100$ from a hardworking son may be seen as a trifle on the island but a fortune on the mainland.

Despite the fact that tourists are paying 100$/night for a hotel room, 100$+/ day on tours and god knows how much on food and trinkets, the average salary for the workers here is around 250-300$/month USD. Where is all this money going? The government takes big cuts in the form of double income taxes (Tanzania and Zanzibar each have taxes that islanders must pay while mainlanders only pay Tanzanian taxes), and licensing fees for anyone who wants to sell, make, display, tour, drive, etc. I saw an actual paddy wagon loaded up with unlicensed street vendors on their way to jail, and my guide said they’ll be right back on the street selling souvenirs as soon as they can. Once the government takes their cut, the owners take the rest, and the owners are mostly foreigners. Several guides throughout my stay told me with bitterness edging their voices about the new development on one of the small islands that was bought up by Indians. Locals never get enough money to invest in property or larger businesses which is a big part of what keeps them trapped in the codependent and often abusive family structures for survival their whole lives.

It reminded me also of a conversation I had with an aid worker who had recently returned from the Congo. The warlords there keep everyone in a state of fear and violence and poverty while reaping the rewards of the mining operations. The mining work gets priority even over subsistence farming, leaving the population without enough food to live on. Many African countries are rich in resources, minerals, fertile land, skilled labor, and yet so often it is mismanaged to benefit only a few while leaving the rest to struggle for less than scraps. There should be enough to go around; the scarcity is artificial. The greed is real.

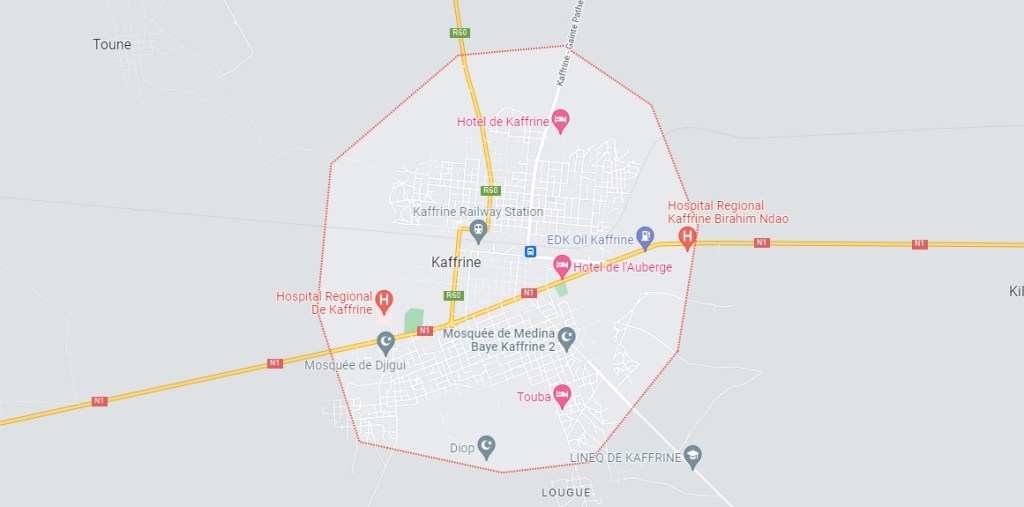

Final Thoughts in Dakar

As I prepare this post, I am 4 days from leaving Senegal to return to the US. Although I would prefer to end my journey on a high note, I feel that would be disingenuous. Living, working, and traveling in sub-Saharan Africa has been one of the most challenging experience of my life so far, but as such, one that will have a large and lasting impact. In addition to the quality of life challenges, it has been an unending revelation of my own biases and privilege, which is a hard pill to swallow. My friends and family, in a well meaning attempt to offer comfort when I’m so obviously discomforted, have used phrases like “living nightmare” to describe the conditions here while saying they simply can’t imagine how anyone could live this way, and telling me how brave and resilient I am. But. These words are not comforting. I am a guest in a place that may be objectively lower on the international quality of life index (yes that’s a real thing), but millions of people still call it home.

People in Africa are struggling with the legacy of colonial war and exploitation that still colors the culture, language, economy, and even religion today. There is no doubt that centuries of foreign rule and resource theft has left deep wounds and little with which to heal them. However, the human spirit is indominable. The people born into this reality are aware of what they don’t have because one thing they do have is enough TV and internet to see the literal and metaphorical greener grass of the northern hemisphere. Yet, every day, they get up and live.

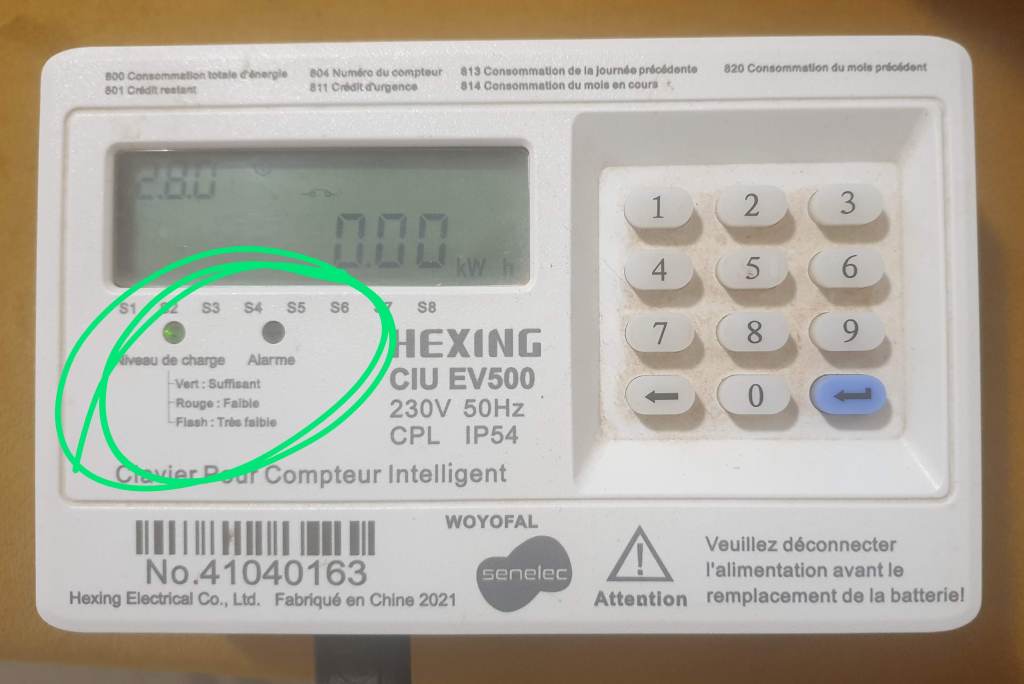

They collect water from a centralized source when the infrastructure fails. They wash clothes in buckets on the front stoop because washing machines are an expensive luxury. There are orphans begging in the streets who will become adults selling peanuts and candy on the roadside. Families struggle to pay high fees for substandard services offered by corrupt politicians and businesses resulting in unreliable electricity, water, and healthcare in even the most developed and cosmopolitan cities. Schools cram 100 students into a room with 20 desks where they learn without computers or enough books. The government of the most stable democracy in the region violates the human rights of its citizens when they complain too much.

But also. They cook delicious food which they share with friends and family when they celebrate holidays, marriages and births. They create music and art in any available space. They stay out late partying and take naps in the heat of the day. Christians and Muslims exchange gifts of food across faiths on their respective high holy days. People gather at public screenings to cheer wildly for their favorite football (soccer) teams and set up casual matches in any open lot or field. They love their children and help their neighbors. They march and protest for better conditions while carrying their national flags because they have national pride and believe their country is capable of more. They open salons on every street and work out in the evenings along the corniche because they take pride in their appearance and wellbeing. They splash in the ocean and laugh with the sheer joy of it. They bring color to the dry and dusty land with bright fabric prints and billowing swathes of bougainvillea that climb every wall and patio.

It is not a tribute to the bravery or resilience of visitors who temporarily partake in a life which so different from the one we were raised to. It is not a fairy tale of the “noble savage” that lets us imagine some kind of mythical innate goodness and moral superiority of the people who have less, and are making the best of it. It is not a whipping post for white guilt where we come to cry and wring our hands about the horrors of the past in order to feel better when we shop fair trade and have someone tell us how good we are for not being racists. It’s just people. The traumas of life affect everyone: individuals, societies, generations. I want to be able to acknowledge the past and honor the pain of another without turning it into inspiration porn or a hairshirt self-flagellation. What do you see when you look at someone who is living a life that you imagine would break you? What are you living with that might break someone else?

In Wolof, the greeting expression often translated as How are you? is “Nanga def?”, but it literally means Where are you?. In English, we have to answer that question with an adjective of value: fine, ok, great, not good, etc. In Wolof, you answer, “Mangi fi.” I am here. I am here.