Stone Town is an architectural love child of Indian, Arabic and Swahili cultures. The narrow maze-like streets car-free (though not cart-free) and stuffed from end to end with life. “Get lost in Stone Town” is another top 10 Zanzibar activity. The whole neighborhood is less than 2km2, bordered by the sea on the west, the Darajani Market on the east, and some fairly uninspiring highways on the north and south. GPS sort of works, but because the streets are so close together and none of them are clearly labeled (or possibly even named) you can only get a general idea of where your destination is. You will get lost trying to get there.

A Brief Historical Context

Zanzibar is an interesting and unique geographical gateway between central Africa and the Arabic and Indian cultures. The trade winds carried ships from India and Arabia then trapped ships on the islands for about 6 months at a time before they were able to sail back. Unlike many other trade centers, where the sailors and foreign merchants were in and out of port in days or weeks, the Indian and Arab merchants who came to the islands of Zanzibar were obligated by the wind to stay for half a year at a time, and so they often married local women, built homes, and had families. Though there is archaeological evidence that the island of Zanzibar was involved in trade with other mainland African cultures, the intercontinental trade seems to have started around the 9th century. There was about 600 years of cultural mixing between the Indian, Arabic, and Swahili people that had ups and downs of who was in charge and who was converting who and who was selling who into slavery, but this is the brief history, so we fast forward to roughly 1500 when Portugal hit the scene.

The 1490s are a bit famous for that trip Columbus took, but he was far from the only European out to find wealth in “unexplored” parts of the world. Vasco de Gama was the first European to reach India by sea, a trade route that required stops along the eastern African coast. Portugal was one of the big European colonial powers and they had their fingers in pretty much every exploited continent. Zanzibar was not only a good resting stop en route to Calcutta, but a source of rare spices and human slaves from the African mainland, which were the big moneymakers in those days. The Portuguese ran Zanzibar for about 200 years, until the late 1690s when the Omani Sultanate took it (possibly at the request of the local Swahili people who thought an Arabic overlord would be better than a European one). Somewhere between 1830-40, the Sultan of Oman moved the capital city from Muscat to Stone Town, and when he died in 1856, he split the empire between his two sons, giving Zanzibar to one and Oman to the other. In a move that surprises no one, they fought about it, but then in a shocking twist, they allowed the will to be arbitrated by the British general protector of India. The Age of Empires remains confusing.

Zanzibar continued as a separate Sultanate until the British decided that actually, slavery was morally reprehensible after all, and that everyone should stop now that they had decided to stop. This didn’t happen all at once, but from about 1822-1873 the British put increasing economic and military pressure on the Sultanate to stop trading in slaves, including trade embargos and the raiding of slave ships. Freetown in Sierra Leone was created to rehome the slaves who were liberated by the British during this time. By 1890, Germany and Britain decided between them that Zanzibar would be a “protectorate” of Britain (which is like colony lite). Finally, in 1963, around the time Britain was being forced to give up on the whole Empire idea, Zanzibar got full independence as a constitutional monarchy. They promptly had a revolution to oust the royals in favor of a representative government, and one year later, merged with the mainland country of Tanganyika to form the modern nation of Tanzania. Despite this unification, Zanzibar remains a separate autonomous region (like Hong Kong and China) with it’s own flag, president and taxes.

First Impressions

My first week in Zanzibar, I decided to stay at a hostel in the heart of Stone Town since it seems to be where a lot of the action on the island is. My ride from the airport (a comedy of errors) tried to just leave me in a random parking lot with a random guy. It felt very sketchy, but I have since learned this is pretty normal and that Stone Town is actually very safe for tourists. In Stone Town, “lost” is a relative term. The streets are close and narrow, but there’s a fair amount of order. There’s the main arterial market streets which are loaded with shops, there are the quiet side streets where locals hang laundry and kids play after school, and there’s the waterfront. You’re only really going to get “lost” in the quiet side streets, and even then only for a few blocks until you’re spit back out to one of the main areas or reach the edge.

I was initially overwhelmed by the number of people talking to me. Unlike Senegal where French is the colonial language, English is the colonial language in Tanzania, and they love greeting tourists with spatterings of friendly Swahili as well. The shopkeepers call out as you pass by, inviting you to look, asking where you’re from, and generally being friendly. Of course they want to sell things, but they don’t physically invade your space and they don’t get mean or angry when you say “no thanks”, they just say “hakuna matata, maybe next time”. There are free range sales people who are arranging tours and excursions and they’ll just walk with you and chat. I got some advice about what to avoid doing and eating while in town, and although I never ended up booking with any of the street tour guides, I quickly came to not mind their chatty presence in my walks through Stone Town the rest of the week.

A Guided Tour

I opted for an Airbnb Experience, again hoping that a more personalized touch would be better than a company tour. It seems like Airbnb in Zanzibar is really just a front for businesses. This may also be related to the rules about tourism and taxi licensing. My spice tour guide explained that it takes a couple years minimum to get the licensing to drive tourists around. Walking tour operators don’t have that concern, but they still have to be able to produce papers if they’re questioned by authorities while leading a group of tourists around. The result is that Airbnb isn’t random locals sharing their culture for a small fee, it’s actual real businesses, and you just have to hope they’re not shady. Reading the reviews helps, but as I learned with my Blue Safari trip is not a guarantee. Thankfully, my Stone Town tour was a win. The other person/people who had booked it never showed up, so I had a totally private tour. The friendly guide was happy to adjust the pace, the amount of time spent at each place, and even the places we went to my personal tastes. He also relaxed and opened up a lot more about the details of life in Zanzibar and Tanzania.

The entirety of Stone Town is a UNESCO Heritage site, and there are a couple buildings in particular (like the House of Wonders) that have their own special status. As a result, everything is always under restorative construction, all the time. UNESCO standards require that repairs must be done in the original work methods with the original construction materials in order to receive funding. This is great in lots of parts of the world, and keeps ancient cultural heritage styles of art and construction alive in places where the local economy might have driven them to extinction. However, in Zanzibar, the original construction was often quick and cheap, and the regular monsoons erode the limestone and coral structures. Walls made of old coral are constantly being replaced and the House of Wonders has been closed for more of the last decade than it’s been open.

In addition to the issue of materials and labor, the currency exchange and corruption are eating away at restoration efforts. The UNESCO funds are issued in Euro but the materials and labor must be purchased in Tanzanian Shillings, so exchange rates affect budgets and cost estimations. In addition, the government officials skim way more than what most countries would consider acceptable graft. My guide expressed a tolerance for “reasonable government corruption” by saying that out of a 20million Euro repair budget, the officials can take up to 2million, but should leave 18 for the work. This 10% skim was his idea of good corruption, but he clarified that in reality the take is much much higher, meaning that most of the UNESCO money goes to lining bureaucratic pockets rather than actually restoring the historical heritage sites.

Doors, Windows, & Walls

The Zanzibari Doors are one of the most famous and easiest things to see on your own while wandering around. Each one is hand carved and unique. They seem to have been a Swahili tradition that was adopted and embellished by the Indian and Arab traders. Most of the accounts of Zanzibari doors I found online seem to have been written by people like myself, visitors who went on the tour, so I’m not sure how historically accurate the information is in details. There’s a serious lack of accessible written history of African cultures. Almost all written records were made by colonizers and traders, and those were generally taken away to live in the basement of libraries and archives in the home countries of those colonizers and traders where they remain in dusty obscurity to this day until a few scholars (also likely not from Africa for economic reasons) decide to sort through them for a PhD dissertation which is itself read only by their peers and advisors, never reaching the general public. Is there a dissertation somewhere on the details of the symbolism of Zanzibari Doors? Possibly? But I can’t find it.

The main differences that everyone knows about are: the Indian style doors which may have round arches and usually have brass spikes, originally used in the Punjab as elephant deterrents, later evolved to a status symbol. The Arabic style doors may have a peaked arch or be square topped, and generally also have some stylized Arabic script, protective prayers from the Quran, engraved on the lintel. The Swahili designs include vines, fish, flowers, and later coffee beans and cloves. My guide told me that pineapples and grapes were a later addition, somewhere around the 1850s, which tracks as 1856 being the year that Zanzibar became a separate Sultanate from Oman.

Though everyone used the doors to signify wealth, each culture had different decorative values otherwise. Arab Muslims were (and in many parts of the world still are) not into external displays of wealth on the home. Exteriors of Arab built homes in Zanzibar are very plain. Windows and balconies are built to protect those inside from the eyes of passersby, and there were even covered bridges between homes to allow the secluded women and children to visit one another without stepping into the public view. The Indians, in contrast, loved to be seen. The exteriors of Indian built homes have flourishes and colors, windows and balconies allow the homeowners to show off their wealth and fashion to the public without going outside.

Modern day buildings and newer doors often incorporate traits from all three main cultural influences for both aesthetic and blended heritage reasons. Architecture isn’t the only thing that blends in Zanzibar. Although Islam is an import from the Arabian peninsula, Zanzibar is currently majority Muslim (while mainland Tanzania seems to be majority Christian). However, the cultural blending of Zanzibari history means that in addition to all the major branches of Islam being represented, Zanzibar also hosts Hindu and Jain temples (of Indian descent) as well as a variety of Christian churches including Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, Adventist, and Pentecostal. I enjoy this photo op of the mosque and cathedral sharing the skyline.

The Freddie Mercury Museum

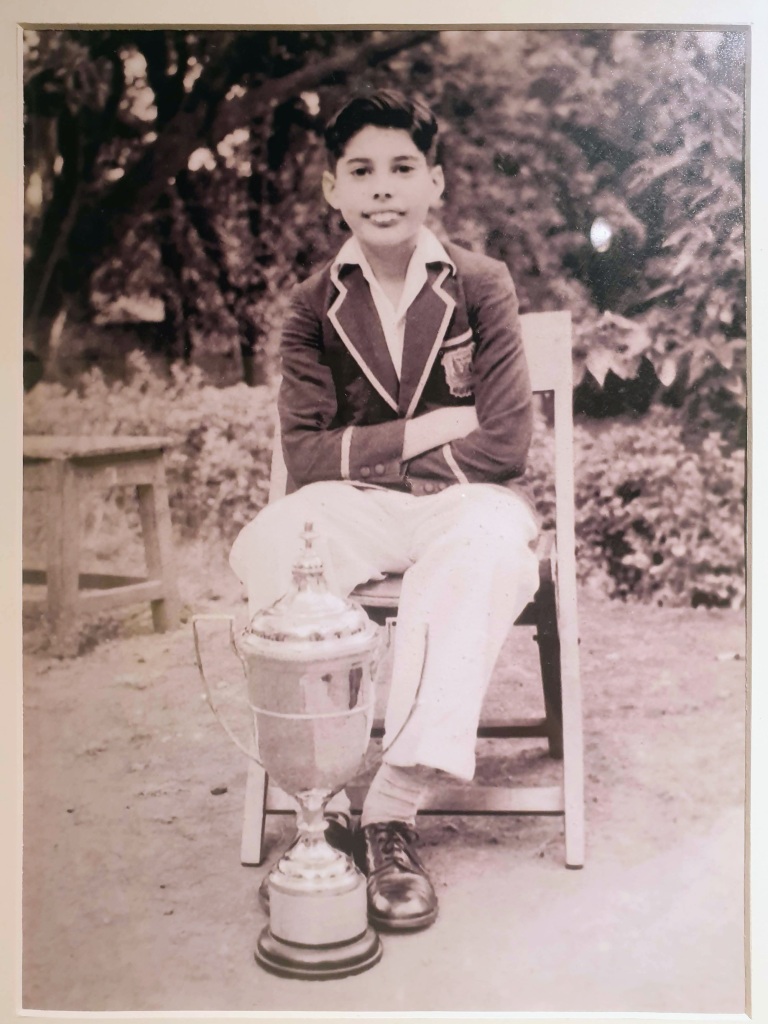

The tour stops out front of the the Freddie Mercury Museum. This is one of the big hot-spots of Stone Town. They are really excited to have a globally famous rock star trace his origin to their town. Freddie was born in Stone Town to Persi-Indian parents. He didn’t actually live there much, since he was in India as a small child, then England for boarding school, but Stone Town claims his birthright. This tiny little museum costs 8$US to enter and takes 15-45 minutes to view depending on how much you want to read and how slow a reader you are. The displays are mostly childhood and family photos as well as album covers. They have an impressive collection of lyric notes, which is kind of cool. There is also a tiny side room that has his famous Wembley concert jackets (the yellow as well as the white with red buckles). I have no idea if anything in the museum is authentic since replicas of these items are pretty easy to get online.

The museum is not what you’d call impressive. I’m biased because I lived with the Seattle EMP (now Mo-Pop) for decades, but even diehard Queen fans would likely feel underwhelmed. Nevertheless, I am happy I spent my money there and I hope more people do because Tanzania is still a place where being queer is illegal, punishable with fines and prison time (up to a life sentence). Freddie is a queer icon. As a bisexual man, his sexuality is often subject to erasure. In the West people tend to forget that he was BI and not GAY, ignoring his relationships with women. In the museum in Zanzibar, there is no mention of his relationships with men, and his relationship with Mary Austin is the only romantic reference. Despite this erasure, I think their pride in Freddie can act as a wedge to allow a discussion of LGBTQ+ rights to take place in Zanzibar and eventually on the mainland, so they can have my tourist money.

“[Queen is] just a name…It had a lot of visual potential and was open to all sorts of interpretations. I was certainly aware of the gay connotations, but that was just one facet of it.”

-Freddie Mercury

“I’m as gay as a daffodil, my dear!”