Ever wonder about the aboriginal people of New Zealand? I had the opportunity to visit a Maori village in Aotearoa and it inspired me to learn a lot more about them. Not everything I have written about the Maori was something I learned in New Zealand. I did a lot of follow up research after I got home to help me understand what I had seen and to put the experiences into a greater context. For the purpose of this blog, I will be mixing the information I found afterward with the descriptions of the experiences to help make the connections clearer.

Feelings & History

When I found myself suddenly spending an extra night in Rotorua, the girls at the reception desk of my hostel recommended the Maori villages as a good activity. This was something I had some strong yet mixed feelings about while I was researching the trip. A lot of websites put one or another village in the top 10 experiences of New Zealand, to the point where it felt like an integral part of the national experience. The issue for me, however, was a leftover white guilt for the way that First People are treated in the US, now and historically. As I write this, tribes are coming together for one of the biggest united protests in our shared history in order to draw attention to a planned oil pipeline that is questionably off their land but would have serious impact on their water. (#NODAPL) Native American reservations already have some of the worst land and water in the continent and are rarely heard when they try to talk about the pollution, the violence against them that still pervades, the lack of access to healthcare or the justice system (only federal courts can hear their cases). Nevermind all the insane horrific murder, rape and mistreatment they suffered for centuries at the hands of European colonialists.

Then, there’s the fact that as a child, I traveled around the American west. It’s not a frontier anymore, but people like to pretend, like to see a show or visit a replica old west frontier town. I went to these and a lot of them are about cowboys and famous historical figures like Wild Bill or Calamity Jane, or Annie Oakley where you can see replicas of the shootout at the OK corral or a modern version of the Wild Bill show. That’s ok, I guess, not that different from going through replicas of colonial villages in New England, it’s a glorified version of history. But I also went to shows about the “Indians”. I watched an outdoor play one night, I don’t remember the story, but I know there were white characters and Native characters, and I remember being riveted. I got a rabbit skin from the souvenir shop and had the whole cast sign it for me… I don’t think I was more than 10 years old.

You can’t go anywhere in the US without being on some tribe’s ancestral land, though. I learned about the tribes as we moved around the country. I learned their words in each new place because white settlers used the names the Natives gave to things long after the people were relegated to reservations, forced to wear western clothes, speak English and go to church. And in the few places where they are reclaiming their place, they are still only known for 2 things: casinos and tourist attractions. Casinos because crazy sovereign land rights make gambling legal on reservations. These buildings are decked out in the tackiest stereotypes of Native imagery with wooden carved Indians in giant feather headdresses adorning the entryways and sacred patterns hanging on the walls, using the images of their culture to draw in suckers. Only slightly less crass are the informational tourism spots where descendants of colonialists can come and see an authentic teepee or wigwam or rain dance. Sometimes they even sell sweat lodge experiences. And as much as I want to learn about the people and the culture, because that is maybe my greatest passion in this life, it feels cheap and tawdry whenever I see these displays outside of museums. This is not to say they shouldn’t live their own culture, but there is a difference between living your lifestyle and putting on a show.

You can’t go anywhere in the US without being on some tribe’s ancestral land, though. I learned about the tribes as we moved around the country. I learned their words in each new place because white settlers used the names the Natives gave to things long after the people were relegated to reservations, forced to wear western clothes, speak English and go to church. And in the few places where they are reclaiming their place, they are still only known for 2 things: casinos and tourist attractions. Casinos because crazy sovereign land rights make gambling legal on reservations. These buildings are decked out in the tackiest stereotypes of Native imagery with wooden carved Indians in giant feather headdresses adorning the entryways and sacred patterns hanging on the walls, using the images of their culture to draw in suckers. Only slightly less crass are the informational tourism spots where descendants of colonialists can come and see an authentic teepee or wigwam or rain dance. Sometimes they even sell sweat lodge experiences. And as much as I want to learn about the people and the culture, because that is maybe my greatest passion in this life, it feels cheap and tawdry whenever I see these displays outside of museums. This is not to say they shouldn’t live their own culture, but there is a difference between living your lifestyle and putting on a show.

Why I decided to go anyway

With all of this heavy history in my head and my heart, it was not an easy decision to visit a Maori village, to cross onto someone’s sacred ancestral land and be… “infotained”. Several factors helped to bring me around.

One, I really like to learn. It’s hard to separate me from an opportunity for knowledge, even if it is uncomfortable.

Two, it turns out the Maori are not “native” to New Zealand. It is believed that the Moriori were actually there when the Maori arrived from Polynesia and were gradually driven South and out (by the Maori) until they finally died off in the 1930s. Unlike the Native Americans who are believed to have travelled to the continent about 10-12000 years ago when there was a land-bridge from Russia to Alaska, the Maori are believed to have arrived in New Zealand only 1000 years ago. I don’t think it gives them less claim to the land, but it does mean that they have more in common with the European colonists than the Native American tribes.

Three, the Maori have not been nearly so hard done by as I had feared. This is not to say they did not suffer at the hands of the British colonists or that new European diseases did not ravage their population, but overall, there was nothing quite like the Trail of Tears or the massive amount of betrayal and backstabbing that went on during the colonization and westward expansion in the US. Captain Cook didn’t even land on Aotearoa until 1769, and for nearly the next hundred years, New Zealand was sparsly colonized, new British arrivals consisting mainly of whalers, seal hunters and missionaries eager to convert the trouserless heathens. Possibly the most damage done to the Maori during this time was the introduction of the gun to their intertribal warfare so that they could kill each other more efficiently.

Fun Facts:

Maori Colonization: The explorer Kupe took a really big boat and ventured across the ocean, leaving his home in search of new land. It’s believed that colonization of NZ from Polynesia was deliberate and slow after this. It took several hundred years of ocean faring boats going back and forth bringing more and more Maori. In fact, the seven main tribes now identify by which boat (waka) their ancestors arrived on. For those who have been wondering about why I keep using other names to refer to NZ, Kupe named the land Aotearoa which roughly translates to “land of the long white cloud”. There are a few legends on why, but no consensus. The seven waka hourua (ocean going boats) and later the seven tribes, are called Tainui, Te Arawa, Matatua, Kurahaupo, Tokomaru, Aotea and Takitimu.

Maori Colonization: The explorer Kupe took a really big boat and ventured across the ocean, leaving his home in search of new land. It’s believed that colonization of NZ from Polynesia was deliberate and slow after this. It took several hundred years of ocean faring boats going back and forth bringing more and more Maori. In fact, the seven main tribes now identify by which boat (waka) their ancestors arrived on. For those who have been wondering about why I keep using other names to refer to NZ, Kupe named the land Aotearoa which roughly translates to “land of the long white cloud”. There are a few legends on why, but no consensus. The seven waka hourua (ocean going boats) and later the seven tribes, are called Tainui, Te Arawa, Matatua, Kurahaupo, Tokomaru, Aotea and Takitimu.

The Treaty of Waitangi was basically an agreement the Maori signed with the British crown stating that New Zealand was under British sovereignty, but that the Chiefs and tribes would keep their own land (selling only to British settlers, no filthy French or Dutch here, please), and that the Maori would have the same rights as British citizens. Of course they’ve been arguing over the terms and ignoring the details since it was signed in 1840, land was stolen anyway and wars broke out, but it was a big deal that the warring tribes came together to deal with the colonists (which did not happen in America) and that they never completely lost the power to leverage this document (also unlike every treaty the US government ever made with Native tribes). I actually passed by the treaty grounds when I was in Piahia, although at the time, I didn’t understand the true historical significance, as I had only US/Tribal treaties as a reference point.

The Treaty of Waitangi was basically an agreement the Maori signed with the British crown stating that New Zealand was under British sovereignty, but that the Chiefs and tribes would keep their own land (selling only to British settlers, no filthy French or Dutch here, please), and that the Maori would have the same rights as British citizens. Of course they’ve been arguing over the terms and ignoring the details since it was signed in 1840, land was stolen anyway and wars broke out, but it was a big deal that the warring tribes came together to deal with the colonists (which did not happen in America) and that they never completely lost the power to leverage this document (also unlike every treaty the US government ever made with Native tribes). I actually passed by the treaty grounds when I was in Piahia, although at the time, I didn’t understand the true historical significance, as I had only US/Tribal treaties as a reference point.

Modern Maori: Are there arguments about land rights, water rights, fishing and hunting rights… and every other aspect of sovereignty? Of course, but it’s much more like an argument between people of (nearly) equal footing than in the US where we’re still ignoring the fact that our reservations don’t have safe drinking water or can’t fish their own streams/ coastlines for a food source. I found lots of news articles about the modern issues between the Maori and the State and the general tone is much more like dealing with a neighboring country or even another political party than anything else. Nowadays Maori language is taught in schools and there are a guaranteed number of Maori seats in parliament based on the numbers of Maori who are enrolled to vote. Meanwhile, Native Americans are struggling to regain their languages from the time the colonists forbade their use, tribes like the Haida in Alaska no longer have any members who can speak the old tongue and the last recordings of their language were made almost 100 years ago. And while there are people of Native descent in congress, they must run as representatives for their state, not for their Tribes.

Modern Maori: Are there arguments about land rights, water rights, fishing and hunting rights… and every other aspect of sovereignty? Of course, but it’s much more like an argument between people of (nearly) equal footing than in the US where we’re still ignoring the fact that our reservations don’t have safe drinking water or can’t fish their own streams/ coastlines for a food source. I found lots of news articles about the modern issues between the Maori and the State and the general tone is much more like dealing with a neighboring country or even another political party than anything else. Nowadays Maori language is taught in schools and there are a guaranteed number of Maori seats in parliament based on the numbers of Maori who are enrolled to vote. Meanwhile, Native Americans are struggling to regain their languages from the time the colonists forbade their use, tribes like the Haida in Alaska no longer have any members who can speak the old tongue and the last recordings of their language were made almost 100 years ago. And while there are people of Native descent in congress, they must run as representatives for their state, not for their Tribes.

Of course the Maori need to keep working to preserve their heritage and the colonial injustices are bad. I don’t want to say their issues are somehow less because other people have it worse. But, it did go a long way toward helping me see that these Maori villages that were offering shows and dinner to visitors were not being exploited or financially trapped into feeling like turning their culture into a show was the only way to earn a living. Rather that they were more like our Native Hawaiian population than our mainland Natives and, so far, I don’t feel guilty about luaus.

I met many Maori in New Zealand. I was surprised, actually at how not white the country is. It’s still about 70% European descent, but the census reckons about 15% of the population is Maori and the remaining 15% a mix of various Asian and non-Maori South Pacific. (In the US, only 2% are Native, and more than half of that greatly mixed.) I gave a ride to a Maori farmer who’s car had broken down and he talked about wanting to do something with his farm to bring in tourists like offering horseback riding tours and lessons. He told me how they used to use Maori language as a secret code when they were kids. Once I learned to recognize the features and not just the tattoos, I saw Maori integrated into every part of New Zealand, often displaying traditional jewelry or smaller tribal tattoos in more discreet places, keeping their culture close, but not ostentatious.

Visiting the Mitai

Armed with a better understanding of the history and a strong desire to learn more, I booked myself a table at the Mitai Maori Village for that evening. The Rotoua area tribes (iwi) are said to all be part of the Te Arawa iwi from the original seven. There are at least 4 villages offering tours, shows, and dinners around Rotorua. I didn’t really do a lot of research into each one because initially I had not planned to go at all. When I did decide to go, I went with the Mitai Village because the hostel I was at was able to get a substantial discount from their regular price. Sometimes we make decisions for very practical reasons.

Armed with a better understanding of the history and a strong desire to learn more, I booked myself a table at the Mitai Maori Village for that evening. The Rotoua area tribes (iwi) are said to all be part of the Te Arawa iwi from the original seven. There are at least 4 villages offering tours, shows, and dinners around Rotorua. I didn’t really do a lot of research into each one because initially I had not planned to go at all. When I did decide to go, I went with the Mitai Village because the hostel I was at was able to get a substantial discount from their regular price. Sometimes we make decisions for very practical reasons.

During my visit to the Mitai ancestral land, two main things happened to me: I learned a lot about Maori which was awesome, and I watched a whole bunch of obviously materialistic tourists treat the whole thing with the respect and solemnity you might expect from a Medieval Times Restaurant, that is to say, none, which was sad.

You’re Saying It Wrong

Now that I’m about 2000 words in, let me start from the beginning. The first thing I learned was that I’ve been pronouncing the word “Maori” wrong my whole life. I don’t know if it was from some well meaning documentary or just some assumptions about the transliteration, but I always said may-oh-ri, with three distinct sylables. I was wrong. It’s a two syllable word that sounds more like maw-ri or mow-ri, the vowel sound is actually about half way between ma and mo and not common in English sounds. It was more like the Korean vowel ㅓ, and the r is more of a flap than a glide with the tip of the tounge tapping the roof of the mouth gently. I had already learned about the strange wh=f issue and now I encountered my first major dipthong (“ao”). I have no idea who Anglisized their language. The Maori had no written language and all of their words are now written using the English/Roman alphabet that is clearly unsuited for the sounds they make, so much so that I didn’t always realize words I heard that night were words I’d seen written on signs around New Zealand as I traveled.

We were greeted at the entrance by a woman in traditional dress and (makeup) tattoo with the Maori greeting “Kia Ora” (key-or-ah) and escorted through to the dining hall for our introductions. Here, our host greeted us again and taught us to say kia ora then proceeded to offer introductions in the native language of every visitor there (although he did have to ask about a few). I thought this was a good idea because it felt like an exchange and not a lecture, and seemed like a good way of engaging the audience and personalizing the experience as much as you can in a group of 50. He told us a little about what to expect for the evening and taught us a few more Maori words, nearly all of which I have subsequently forgotten, but it was fun and as an amateur linguist I really liked having the opportunity to hear and practice the Maori phonology.

We were greeted at the entrance by a woman in traditional dress and (makeup) tattoo with the Maori greeting “Kia Ora” (key-or-ah) and escorted through to the dining hall for our introductions. Here, our host greeted us again and taught us to say kia ora then proceeded to offer introductions in the native language of every visitor there (although he did have to ask about a few). I thought this was a good idea because it felt like an exchange and not a lecture, and seemed like a good way of engaging the audience and personalizing the experience as much as you can in a group of 50. He told us a little about what to expect for the evening and taught us a few more Maori words, nearly all of which I have subsequently forgotten, but it was fun and as an amateur linguist I really liked having the opportunity to hear and practice the Maori phonology.

The Quick Tour

Next we broke into smaller groups and bundled outside to see some of the village. Our group first visited the boat displayed by the front gate. Our guide explained to us about the word “waka” (boat) and the three most common types of waka for daily use (fishing and transporting goods), for war, and for long ocean journeys. She pointed out to us the way in which this particular waka was made using planks and that was how we could tell it was a replica and not a traditionally made waka. In fact it was the prop from the movie The Piano. I appreciated the fact that they were so upfront about the fact it was a replica, using the movie prop to point out the similarities and differences between the prop and a traditional waka. It felt honest. Film and museum replicas are great for showing off history, but should never be passed off as originals.

Next we broke into smaller groups and bundled outside to see some of the village. Our group first visited the boat displayed by the front gate. Our guide explained to us about the word “waka” (boat) and the three most common types of waka for daily use (fishing and transporting goods), for war, and for long ocean journeys. She pointed out to us the way in which this particular waka was made using planks and that was how we could tell it was a replica and not a traditionally made waka. In fact it was the prop from the movie The Piano. I appreciated the fact that they were so upfront about the fact it was a replica, using the movie prop to point out the similarities and differences between the prop and a traditional waka. It felt honest. Film and museum replicas are great for showing off history, but should never be passed off as originals.

After admiring the waka, we headed over to the cooking pit. Here, our hosts had dug a deep pit in the earth which was filled with hot coals. The food was carefully wrapped and lowered on a tray into the pit, then covered with blankets to keep in the heat, cooking what would soon be our dinner. This is one of two historically traditional methods the Maori used for cooking, the other being to use the geothermal heat of the region to steam the food instead of a manmade fire. I understand at least one village in the area still has access to a nearby hot pool they use to prepare dinner for guests with, but the Mitai lived with a vibrant freshwater spring rather than a geothermal one. Our guide told us that although the Maori cooked this way in the past, that mostly what they ate were the native ground birds which are now all extinct or protected and so the only traditional food in the meal would be the sweet potatoes (kumara) and that the rest of the chicken, lamb, potatoes and stuffing were all brought in from the British settlers. I suppose to some, this revelation may have been a disappointment, finding that our Hangi feast was really made of familiar food, but again, I appreciated the honest discussion of history and the unique way that a living culture had adapted to the changing times far more than any fake recreation of an imaginary past. Our guide said a prayer in Maori over our meal, before covering it back up and leading us once more into the dining hall.

After admiring the waka, we headed over to the cooking pit. Here, our hosts had dug a deep pit in the earth which was filled with hot coals. The food was carefully wrapped and lowered on a tray into the pit, then covered with blankets to keep in the heat, cooking what would soon be our dinner. This is one of two historically traditional methods the Maori used for cooking, the other being to use the geothermal heat of the region to steam the food instead of a manmade fire. I understand at least one village in the area still has access to a nearby hot pool they use to prepare dinner for guests with, but the Mitai lived with a vibrant freshwater spring rather than a geothermal one. Our guide told us that although the Maori cooked this way in the past, that mostly what they ate were the native ground birds which are now all extinct or protected and so the only traditional food in the meal would be the sweet potatoes (kumara) and that the rest of the chicken, lamb, potatoes and stuffing were all brought in from the British settlers. I suppose to some, this revelation may have been a disappointment, finding that our Hangi feast was really made of familiar food, but again, I appreciated the honest discussion of history and the unique way that a living culture had adapted to the changing times far more than any fake recreation of an imaginary past. Our guide said a prayer in Maori over our meal, before covering it back up and leading us once more into the dining hall.

Here he went more into details about Maori culture, language and history. He asked us to choose a “chief” from among ourselves to represent us as a visiting tribe. He told us the Maori called foreigners “the tribe of the four winds” or Ngā Hau e Whā, to represent that we come from everywhere. There were more than 21 different countries represented in the audience that night. Women are not allowed to be chiefs or you can be sure I would have raised my hand, but two men both volunteered and the guide decided to have a contest between them.  He taught them how to make the traditional war face which involves opening one’s eyes as wide as possible, sticking out the tongue toward the chin and doing an aggressive war cry. One of the men took this task quite seriously, doing his best to make an intimidating face and sound as he was shown, buy the other (and younger) was too cool for school and sadly sought audience attention by laughing at the process and doing a poor imitation of the war face, perhaps unwilling to look foolish, but in the end failing. We were asked to vote by applause and the man who went all out won by a landslide, which was nice, because I felt like he would at least take his duties as our chief for the night seriously and not treat it like some kind of opportunity for laughs.

He taught them how to make the traditional war face which involves opening one’s eyes as wide as possible, sticking out the tongue toward the chin and doing an aggressive war cry. One of the men took this task quite seriously, doing his best to make an intimidating face and sound as he was shown, buy the other (and younger) was too cool for school and sadly sought audience attention by laughing at the process and doing a poor imitation of the war face, perhaps unwilling to look foolish, but in the end failing. We were asked to vote by applause and the man who went all out won by a landslide, which was nice, because I felt like he would at least take his duties as our chief for the night seriously and not treat it like some kind of opportunity for laughs.

Maori Greetings

The guide then explained that when we went into the meeting hall (performance hall too), their chief would meet our chief. When two families or tribes meet, one puts a small offering on the ground (often a silver fern leaf). If the visiting chief picks it up, it is a sign that they are peaceful and pleasantries, trading, or feasting can commence. If the visiting chief refuses to pick it up, it is a declaration of the intent for war, and fighting promptly ensues. The next thing he showed us was the Maori greeting. We had already learned how to say kia ora (key-oh-ra), which means not only hello, but also goodbye and is a general well wishing like “be well” or “good health to you”. If someone says kia ora to you, it is polite to say it back. Next he taught us the body language that goes with it.

In the west, we shake hands, and in Asia, people bow, but when the Maori meet they touch foreheads and noses at the same time. Called the hongi (not to be confused with hangi, our dinner), it is an intimate greeting that breaks down the barriers of personal space immediately. The touch is done twice. On first touch, you do not breathe. This stillness is for the dead, for those who have come before and gone beyond. On the second touch you breathe, mingling the breath of life (ha) which can also be seen as a co-mingling of spirits. It is a representation of the creation of the first human. Tane (the giant tree who separated his parents to make room for life) created a woman (yeah, first human is a woman here) from the earth and breathed life into her. Once this is done, visitors are considered part of the village for the duration of the visit and share in all rights and duties that the villagers themselves do.

In the west, we shake hands, and in Asia, people bow, but when the Maori meet they touch foreheads and noses at the same time. Called the hongi (not to be confused with hangi, our dinner), it is an intimate greeting that breaks down the barriers of personal space immediately. The touch is done twice. On first touch, you do not breathe. This stillness is for the dead, for those who have come before and gone beyond. On the second touch you breathe, mingling the breath of life (ha) which can also be seen as a co-mingling of spirits. It is a representation of the creation of the first human. Tane (the giant tree who separated his parents to make room for life) created a woman (yeah, first human is a woman here) from the earth and breathed life into her. Once this is done, visitors are considered part of the village for the duration of the visit and share in all rights and duties that the villagers themselves do.

River Raid

With our chief prepared to meet the Mitai chief, we headed out into the bush to watch the warriors paddle their waka down the stream in a recreation of a traditional war party. This waka was made in the traditional manner, unlike the movie set replica at the front gate. Perhaps in the summer, this part of the performance is more visible. I’ve seen some pictures online that look like they are happening in daylight, but during August, the sun was setting around 6pm every night and it was quite dark by the time we were led down to the stream. Nonetheless, the warriors in the waka had torches (fire, not electric) and it was impressive to see them coming down the stream, chanting and going back and forth between paddling and using the oars in a type of dancing display.

With our chief prepared to meet the Mitai chief, we headed out into the bush to watch the warriors paddle their waka down the stream in a recreation of a traditional war party. This waka was made in the traditional manner, unlike the movie set replica at the front gate. Perhaps in the summer, this part of the performance is more visible. I’ve seen some pictures online that look like they are happening in daylight, but during August, the sun was setting around 6pm every night and it was quite dark by the time we were led down to the stream. Nonetheless, the warriors in the waka had torches (fire, not electric) and it was impressive to see them coming down the stream, chanting and going back and forth between paddling and using the oars in a type of dancing display.

Sadly, my cameras are really lousy at low light. Maybe one day I’ll run a go-fund-me for a new one, but somehow every time I come face to face with the choice of spending my money on a new camera or on a new country experience… there is no actual competition. As a result, I have pretty old cameras. I usually am able to share my own photos of the places I’ve seen, but in low light the best I can do is share the photos of people with expensive cameras who went to the same places to give you a better idea of what we saw.

Show Time

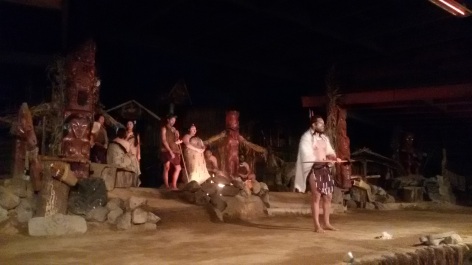

After the outdoor display, we headed into the performance hall. It was somewhere during this time that I started getting flashbacks to my childhood wild west/cowboys and Indians shows. The stage was set up to look like a Maori village, and once again, the guide was quite clear that it was a set and not real. The performance started with singing and dancing, then the cheif came out and gave a speech in Maori that of course none of us understood. While all the Maori performers were wearing traditional costumes, it struck me at once how different the cheif’s clothing was, especially the white fur cloak he wore. New Zealand has only one native land mammal, which is the bat, so where did this fur come from? It turns out that the Maori brought dogs, kuri, with them from Polynesia. The dogs were rare and their fur was prized as one of the elite materials for chieftain cloaks (along with fur seal skin), and because white was a common kuri coloring, I expect this was meant to represent a white kuri skin cloak and was quite prestigious indeed.

After the outdoor display, we headed into the performance hall. It was somewhere during this time that I started getting flashbacks to my childhood wild west/cowboys and Indians shows. The stage was set up to look like a Maori village, and once again, the guide was quite clear that it was a set and not real. The performance started with singing and dancing, then the cheif came out and gave a speech in Maori that of course none of us understood. While all the Maori performers were wearing traditional costumes, it struck me at once how different the cheif’s clothing was, especially the white fur cloak he wore. New Zealand has only one native land mammal, which is the bat, so where did this fur come from? It turns out that the Maori brought dogs, kuri, with them from Polynesia. The dogs were rare and their fur was prized as one of the elite materials for chieftain cloaks (along with fur seal skin), and because white was a common kuri coloring, I expect this was meant to represent a white kuri skin cloak and was quite prestigious indeed.

He presented the peace offering as we were told to expect, and our “cheif’ picked it up accepting the peace. He introduced us (his tribe) and thanked the Mitai chief for hosting us on their land. Then they performed the hongi (touching nose and forhead) and our chief was able to return to his seat. Following the formal introductions, the Mitai chief switched to English and gave a brief introduction of himself and the tribe, reminding us all that the Maori now live in modern houses, wear regular clothes and enjoy using facebook, and that all of that night’s show was a way of demonstrating their history and traditions that are no longer practiced except for purposes of historical preservation or special significance. He was easygoing and had a good sense of humor that kept the audience engaged, but it was still sad to me to see the fact that their history was being almost Disneyfied for our consumption.

The Action Song

The performance is known as waiata a ringa, or action song. In the early 1900s, there was a movement to revive traditional Maori music that added dancing and the guitar to the traditional singing, and eventually developed into a standard performance used all over Rotorua today that includes a sung entrance, poi, haka (“war dance”), stick game, hymn, ancient song and/or action song, and sung exit. Our performers (kapa haka) did not do it in exactly that order, but really close, and nowadays the action song is used in competitions between iwi (tribes) around New Zealand; it’s not just a tourist attraction.

After the sung entrance and the chief’s introductions, they introduced traditional Maori instruments of which there are two main kinds: melodic and percussive. Melodic instruments (rangi) include flutes made from wood or bone, gourd instruments that are blown into or filled with seeds and shaken, and trumpet instruments made from shells. These are considered the domain of the Sky Father but each group and specific instrument has it’s own god/goddess or spirit associated with it. Percussive instruments (drums, sticks, poi -the white flaxen balls on strings, and a type of disc on a cord) are considered the heartbeat of the Earth Mother.

After the sung entrance and the chief’s introductions, they introduced traditional Maori instruments of which there are two main kinds: melodic and percussive. Melodic instruments (rangi) include flutes made from wood or bone, gourd instruments that are blown into or filled with seeds and shaken, and trumpet instruments made from shells. These are considered the domain of the Sky Father but each group and specific instrument has it’s own god/goddess or spirit associated with it. Percussive instruments (drums, sticks, poi -the white flaxen balls on strings, and a type of disc on a cord) are considered the heartbeat of the Earth Mother.

They showed us how some of the percussive instruments like the poi and the sticks had started out as training activities to strengthen the warriors, but had quickly been adapted as games and dances by the women. The poi were used in dances, but also to imitate sounds the Maori people heard around them, including the more modern sounds of the imported English horses and the railway. The short sticks were used in group dances combining rhythm and agility as the men and women tossed the sticks around the circle while singing and beating out the time (the stick game).

They also performed some beautiful songs that included the hymn and the ancient song as well as some lighter-hearted love songs. One of the cuter love songs included the lyrics, “hey pretty lady, your boyfriend he’s no good, so come with me instead”. The hymns were not translated for us, so I’m not sure exactly which gods they were honoring, but at least one of the ancient songs was a sort of Maori “Romeo and Juliet” about a pair of star crossed lovers named Hinemoa and Tūtānekai. They lived in villages in Rotorua, across the lake from one another, and their families forbade their marriage. Unlike Shakespeare’s famous couple, however, Hinemoa and Tutanekai had a happily ever after, because after his family had taken Tutanekai’s waka to stop him, Hinemoa swam across the lake to reach him instead.

The performance is far from over, but this post is reaching my self imposed limit for avoiding TLDR syndrome. I hope you’ve enjoyed what you’ve learned so far. I’m not posting an album on Facebook for this experience because my photos are too dark, but you can find my YouTube Channel if you want to see more videos of this and other travels. Part 2 is coming soon!