It has become unavoidably obvious that I am caught in the grip of some of the worst “rejection phase” culture shock I can remember. I was in denial about this up until this past Monday, but I can’t keep lying to myself about it. I was already upset that I didn’t get a “honeymoon” phase for Senegal, and I’ve spent almost every day since arriving here telling myself to stick it out because it will get better when… when I find an apartment, when my classes start, when the weather cools off, when I meet more people, when I finish this conference… it’s a never-ending goalpost-shift that I’m doing to myself. The wildest part about finally realizing that my anger, doubt, and frustration is “normal culture shock” is that it doesn’t make me feel any less angry, doubtful or frustrated… it just makes me feel very predictable and if anything even more angry, doubtful and frustrated that after 8+ years living abroad I’m still susceptible to this kind of extreme emotional wreckage.

What Is Culture Shock?

There’s a million articles about this, so I’m not going to go over every detail here. The most important things to know about culture shock are a) it’s not something you can just willpower yourself out of, and b) it follows a pattern within parameters. It’s a lot like grief or trauma response in this way. Most people know the “5 phases of grief”, but fewer know the phases of culture shock.

- honeymoon – “everything is awesome” or at least quaint, charming, or some other positive adjective

- rejection – “everything sucks”

- adjustment – “maybe I can make this work”

- adaptation – “I got this”

- reverse culture shock – “home doesn’t fit the same anymore”

These are often presented as a U-curve but in reality we know it as a rollercoaster that never ends, but just goes around and around and sometimes leaves you stuck hanging upside-down.

Much the same way that reaching the “acceptance” stage of grief doesn’t mean you magically stop feeling sad about the loss of your loved one, reaching “adaptation” doesn’t make you suddenly immune to culture shock.

A lot of the talk about culture shock is on a timeline of a year, roughly in quarters, and I think that’s because a year is a very standard time of living abroad for study or work. I’ve seen people on holiday pass through all four stages in a week, going from loving everything on Monday to nearly getting on a plane to fly home on Wednesday to navigating the public transit system and haggling with the street vendors by Saturday. Then there’s long term expats like myself who never really stop fluctuating through the effects of culture shock, but experience them in less extreme forms.

The brain goes through a bunch of changes when we leave our familiar surroundings. New neural connections are formed, chemicals and hormones are released in new and different ways and amounts. The honeymoon phase may just be extra dopamine and serotonin, and the rejection phase may be extra adrenaline and cortisol. It’s normal to seek the cause for any new emotion in our present environment. I learned about it while studying the trauma phenomenon of “emotional flashbacks” in which we experience an emotion as a result of past trauma but without the accompanying memory, we ascribe the cause of the emotion to the present, to whatever happened just before we started to feel it (the trigger).

When we are still new to a host culture, it’s easy to assign responsibility for any extra emotions (pleasant or un-) to the most obvious changes in our condition – the new culture. When we live in a foreign environment for years, we still experience the extra emotions, but tend to cast about for things within our lives like work or personal relationships which may have changed more recently. It’s classic the correlation/causation mix-up.

For a really long time now, whenever I have had brain changes resulting from culture shock, I didn’t think about them as being related to the specifics of Korean culture, but was able to see them as part of a broader pattern of the expat emotional roller coaster. I was having culture shock, but it wasn’t manifesting in the stereotypical ways. Now, I find myself suddenly having some very textbook-example culture shock symptoms, and I almost didn’t see it because I thought it was just for new travelers. Silly Rabbit, culture shock is for everyone.

Realizing I’m a Stereotype

At lunch the other day, my American colleagues patiently listened to me explain why I was having such a hard time here, and then while agreeing that my observations were valid, also pointed out that my emotional reaction could be culture shock. I gave it very little thought at the time, but it sat in my brain, and by the time I got home that afternoon (grumpy, exhausted, and questioning my life choices) I decided to do a little Googling. At first, I wasn’t finding any resonance. Yes, I missed my honeymoon phase because of housing and weather issues, and I had some complaints about things like chronic lateness and haggling for taxis, but I had plenty of examples of Senegalese culture that I appreciated. I love the food, I really enjoy driving along the corniche and watching the ocean, I like the way that everyone grows flowers to give color to the otherwise sand colored land. I was able to enjoy good nights out, and butterfly migrations, and students having fun. Surely I couldn’t be in this “hate everything” phase and still enjoy all that. Surely my litany of complaints were grounded in objective reality and not in an involuntary emotional response? Right?

Most people focus on the part of the “rejection” phase that centers around negative thoughts and feelings toward the host culture, but it’s not the only thing. There’s a whole pile of physical and mental health issues that come with this phase, especially if one is making the conscious effort to resist cultural judgement.

FATIGUE, ILLNESS, EATING/SLEEPING ISSUES – I wrote before about Bessel Vander Kolk’s seminal work The Body Keeps the Score. That book is about trauma manifesting in the body, but it carries the broader message that all kinds of unresolved stresses will come through as physical symptoms, especially in the form of chronic fatigue, chronic pain, eating/digestive issues & sleeping issues. Culture shock stress is no exception.

Am I extra tired because it’s hot AF, and because everything takes more time and energy to do, or because of culture shock? Am I feeling icky because of new local bacterial strains or because of culture shock? Am I not sleeping well because it’s a new apartment or is my insomnia acting up because of culture shock? Eating ice cream and bread for dinner is probably culture shock, but my recent bout of “I wanna die” fever/chills/aches/bed-to-bathroom/please-let-the-antibiotics-work-soon illness is probably the result of some local microbes my body has no immunity to.

MOOD SWINGS: ANGER, DEPRESSION & ANXIETY – Everything makes me grumpy, I have no resilience for minor obstacles. I hit fight, flight or freeze waaaay sooner than my own personal baseline. This results in some unhelpful reactions like loosing my temper at drivers who can’t use GPS or mentally checking out when I need to be focusing. Are my feelings of grumpiness proportional to the circumstances? Maybe sometimes? I mean, how many cockroaches do you have to squish before it makes you crazy? Is it reasonable to get angry when someone leaves your window cracked and the mosquitoes attack you in your sleep? What about when the neighbors kids get in a screaming match under your window for the 15th time this week, or they are redecorating next door and spend hours every day with hammers and drills? Am I grumpy all the time because of bugs and dirt and noise or because of culture shock?

I’m no stranger to anxiety either, but I was very interested to find that culture shock anxiety comes in new flavors like special concerns about water/food safety, a preoccupation with being scammed or robbed, and an obsession with cleanliness. I am not gonna lie, having to boil all my water even to brush my teeth means I spend more time thinking about it. I also sanitize my produce, which is not a thing I’ve done in other places (wash yes, but here we soak it in a mild bleach solution and rinse it with boiled water, it’s way more). I am also finding myself preoccupied with the bugs that I find crawling around. Intellectually, I know it’s just part of living in a climate like this. Even living in the US southern states you’ll be living with bugs, but I have noticed I think about it more here.

I’m starting to see that culture shock and emotional flashbacks have a lot in common. They are both strong emotional states which are frequently misattributed to coincident actions or environmental conditions. After I learned about the existence of emotional flashbacks, I had to start learning how to evaluate triggers. Sometimes, I’m triggered by things that are genuinely innocuous. In those cases, my emotional response is 100% not caused by the trigger. Other times, people do things that are objectively crappy and I have to sort out how much of my emotional response is flashback and how much is reasonable given the circumstances. I have to learn what a proportional emotional response feels like.

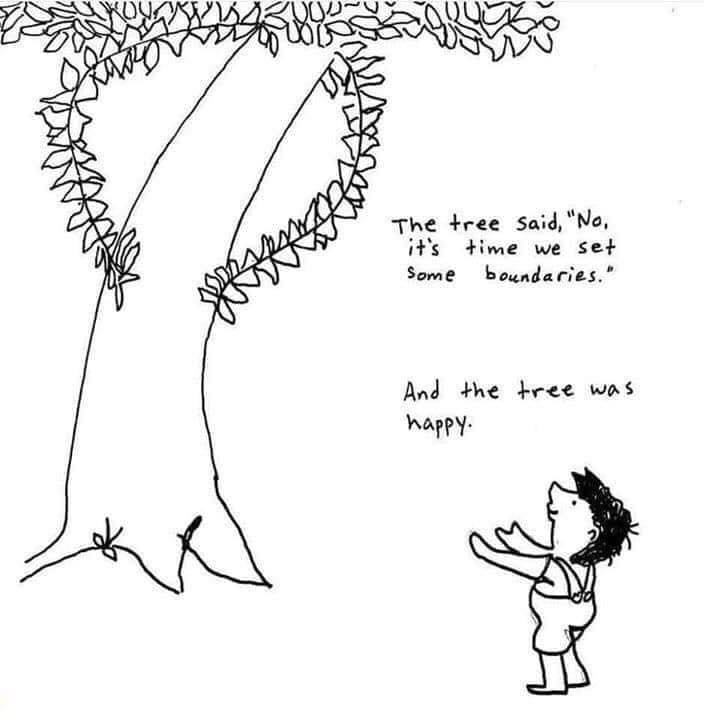

It’s reasonable to be upset and express disappointment when someone flakes on plans, but not reasonable to scream and cry for days about it. It’s reasonable to be frustrated that professional drivers can’t read maps, but not reasonable to yell at them about it. Why allow ourselves to be upset or angry at all if it causes so much trouble? Our anger protects us from abuse and harm. It’s reasonable to stop making plans with a person who never follows through, or to cut a person out of your life who won’t stop hurting you. It’s reasonable to leave a job that has a hostile work environment or move to a new city if the pollution is wrecking your health. Our proportional emotional responses serve to help us establish and maintain boundaries and ask for what we need in life to be comfortable and safe. The trick is identifying those when you’re in a state of emotional dysregulation.

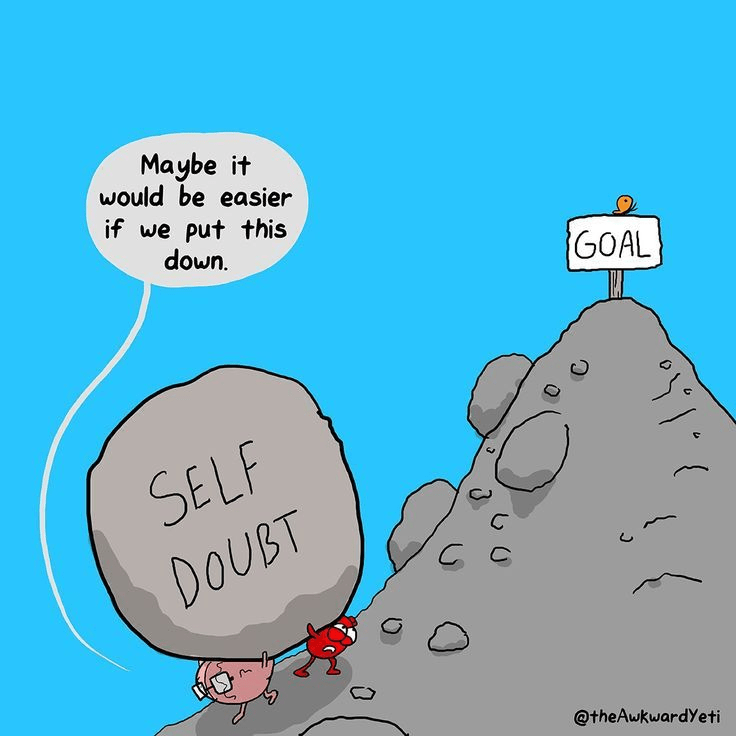

SELF-DOUBT – This is the one that completely ate my brain when I found it. I was sitting around thinking things like “maybe I’ve made a terrible mistake”, “maybe I’m not strong enough to meet this challenge”, “maybe I’m a spoiled white-girl American after all”, “I don’t know if I can do this again, but I feel like a loser for not wanting to take advantage of this opportunity” and then I read this: Culture shack manifest as…

- Questioning your decision to do this work

- Feeling more shy or insecure than normal

- Questioning long-held beliefs about religion, gender, morality, or other core convictions

- Feeling like you’re an imposter

- Questioning your ability to overcome adversity

Questioning My Decision to Do This Work

I already felt like the work I was doing in Korea was pretty darn meaningless, but the ability to travel the world on my holidays made up for a lot. During the pandemic when I was teaching required English classes online to students who were not interested in learning or using English and generally slept or played video games during the class, and I was totally unable to travel, the pointlessness of it all was eating away at me. When I was offered this Fellowship I thought, “well, no matter that Senegal will come with heat and dirt and bugs and other hardships, I will be doing something meaningful, and not in a “White Man’s Burden” way by imposing my own values, but by providing support to locals who are building meaningful educational programs themselves.” Reality has yet to measure up to this expectation.

The work I’m doing is if anything less meaningful. Meeting veterinary students one day a semester to promote the value of English education when no English education is available to them and no school resources or faculty members are allocated to help them is a waste of energy to promote a façade. Don’t get me wrong- I love meeting the students. I love watching them have fun in English and shake off some of the language anxiety, but I am frustrated by the total lack of ability to form rapport, or to provide growth opportunities. I feel like someone at State is going tot read this and ask me why I didn’t ask for more help from the school or the program, but the reality is, I’ve asked for help and been told “Inshallah, maybe next year” and due to the long list of culture shock symptoms listed above, I don’t have the energy or conviction to keep banging my head into that particular wall. And the idea that I, the foreign visitor, should be the one to spearhead the change or improvement or new program is exactly the kind of crap Kipling was advocating in his famously racist poem that I am working so hard to NEVER exemplify.

Feeling More Shy or Insecure Than Normal

I don’t know if I will ever actually be “shy”, but I have definitely had a lot of thoughts of insecurity – not only related to my ability to do the work or overcome the challenges, but in a social way. I have a lifetime of misreading social situations, and over the past many years I had come to a kind of peace with that where I became ok with people wandering off or didn’t listen because I just decided I would spend my energy on the people who wanted me around and showed it. I find that the people who stick around are a much more fulfilling category of relationship and I’m able to enjoy the more causal company of others with no expectations.

Now in Senegal, I’m suddenly I’m having the “are they secretly laughing at me when I’m not in the room” thoughts again. I feel like I’m imposing when I ask for help from the people whose job it is to help me. I feel like I’m incompetent in communicating when people say they can’t understand my French (it’s objectively accented but not unintelligible). I have to psych myself up to place delivery orders because I’ll have to talk on the phone. “I don’t know if I can do this” is starting to feel like a mantra, and it’s not a good one.

Questioning Long-Held Beliefs About Morality or Other Core Convictions

Questioning long held beliefs is a hobby of mine. I love reading/watching stuff that makes me think. I love the fact that living abroad makes me question myself. I love that teaching university students makes me constantly aware of changing values by generation. I have questioned my religion, gender, and sexuality to death, but I still managed to find a new morality / core identity issue to question here in Senegal: my privilege, my biases, my culturally baked-in racism, the morality of existing as a person whose privilege comes from the multi-generational exploitation of the country I’m in (one of the biggest slave ports was here in Dakar), and my responsibility within a problematic system.

It started because things are hard and I complain, and I end up feeling very “spoiled white girl” complaining about difficult, expensive, or uncomfortable things, which then makes me feel guilty, which then makes me self referentially aware of my white guilt, and I get sucked into a moral rabbit hole that would give Chidi Anagonye a very upset tummy.

When I complained about stuff in Korea, it was cultural not economic. Things were not better or worse, they were just different. Here, my lowest acceptable standards for long-term quality of life are actually quite high relative to the local people’s lived experiences, and it’s not something they can afford to change. One could argue that it’s a class/economic issue separate from the question of race, but the reality is the reason most of Africa is in poverty is because of the exploitation of the slave trade and colonialism.

Even though I experienced poverty by American standards, I still grew up with relative wealth and privilege that came directly from the historical destruction of this culture and economy, and now I’m so spoiled by all that privilege that the way many of these people live seems substandard to the point of discomfort and even disgust to me. Do I have any right to complain? And yet I can’t make myself comfortable with the local quality of life just by acknowledging this disparity. I always say it’s not the Pain Olympics and we shouldn’t engage in comparative suffering, but I can’t help wonder if I’ve become the global version of the kid who is mad they only got the second newest iPhone for their birthday.

There’s pressure to conform to the white savior trope, too. I am pushing back against that, but I can feel it coming not only from the program and the Embassy, but also from the locals. I know my intentions are good in being here, but there’s a huge accountability gap between “not purposely making it worse” and “not actually making it worse”. I can’t say for sure that my presence here isn’t making things worse. The school ditched their local English teacher when they got a foreigner, and they don’t have any plans to hire real English faculty (I’m not working here as a full time teacher), so now the students have a “meet the native speaker” day instead of a real class with a Senegalese teacher. It was supposed to be “in addition to”, but this is what happens when people assume the white/American/native English speaker is automatically a superior resource. When I go to conferences and speak, I’m given preference simply because I’m perceived as a foreign expert, and I have to figure out how to balance my desire to further my own career with my responsibility not to take away time/attention/resources from locals.

Regardless of my intentions before arriving (when I didn’t yet understand the full reality we can argue I was not making a moral transgression) but now that I know do I have a moral obligation to take a different course of action? We hold people accountable for being a knowing and complicit part of a damaging system, so the question is: is this a damaging system (in the assumption that we as Americans occupy a position of needing to step in and help or manage programs in developing nations, and are we helping in the sense of following the locals’ lead or “helping” in the sense of telling them what to do?), and is staying and doing my best more or less morally responsible than leaving this “white man’s burden” parody of diplomatic relations?

I don’t expect an answer, it merely illustrates the point that my “questioning moral and core beliefs” switch has been fully engaged in this round of culture shock.

Feeling Like I’m an Imposter

A lot of “former gifted children” feel this. Being told for years that you’re smarter and more driven and more creative and generally better than your peers is not actually helpful, as it turns out. I managed to maintain the illusion until I got to grad school, where I was suddenly surrounded by all the other gifted kids, many of whom also had major economic advantages in terms of private studies, internships, and study abroad programs and were leaving me feeling like I didn’t belong at all. My polyglotism is a chronic source of the strange see-saw of confidence/imposter syndrome. Compared with the average American, even the average American with my equivalent education, I have awesome language skillz. I can get unlost in 7 languages. However, I can’t have a reasonable conversation in more than 2-3 and I can’t have an advanced topic discussion outside of English. Compared to most of the people I meet in academic or government programs, I’m a language idiot. Every one of the 6 Fulbrighters (22-24 year-olds) who I met at orientation is fluent in French and several are already passable in Wolof. They were selected for the program in part for this skillset, while fluency was barely a consideration for my position and I shouldn’t feel bad because I was selected for a highly competitive program based on a lifetime of education and experience, but I feel like I’m somehow less qualified to be here than the new college grads. Imposter!

I also feel that the expectation that I’ll be organizing projects, mentoring teachers, and presenting at conferences is in a big way setting me up for another round of “I don’t belong here”. That’s playing back into the insecurity, but insecurity and imposter syndrome are best pals. After all, if I’m not actually qualified to do this and people figure that out, they will dislike me, right? So far I’ve been able manage the projects I’ve been asked to take on (feeling like a faker the whole time); however, there’s no doubt that the imposter syndrome is stopping me from asking for more opportunities or creating more for myself, which contributes to the feeling that I’m not doing any meaningful work, which contributes to the self doubt of whether I should be here at all. It’s a vicious-tangled-circle-web culminating in…

Questioning My Ability to Overcome Adversity

Everything I complain about, all the feelings of doubt and inadequacy, all the physical discomfort, the obstacles to personal and career goals, and the ongoing struggle with depression and anxiety are ADVERSITY, so as soon as my ability to overcome adversity comes under fire, it makes all those other issues that much bigger and by definition insurmountable.

When we are young, we feel immortal and almost arrogantly confident. We don’t know enough to know that’s supposed to be impossible so we do it. As we age, we learn our limitations through painful consequences. Perhaps 25 years ago, my faith in my ability to overcome was based in youthful grit and stubbornness, but these days it comes from a place of experience. I have overcome adversity in the past, and any time I can compare my current adversity to a past adversity which has already been conquered, it’s easy to have faith that I’ll make it. The reverse side of the “past experiences” coin is that my anxiety is also based on experience: “this horrible thing that most people only imagine and isn’t actually very likely has already happened and is therefore 100% likely and reasonable to feel anxiety about”.

Of course, at some point everything we overcome has to be overcome for the first time. Artists don’t start by painting museum quality oils. Athletes don’t start by running a marathon. We start small and build up. It’s true that we get older, we become more risk averse, but I can continue to do things like “quit my job and go to a foreign country” because my experience tells me that is actually a low risk activity for me. Before coming here, I thought that my past experiences of living in China and Saudi and travelling around the Middle East and Southeast Asia would prepare me for the challenges I’d face in Senegal. Now I’m wondering if there are just some adversities I have Murtaugh Listed out of being able to handle

Psychological Side Effects

There’s one more factor about living in Africa that is unique to this continent: anti-malarials. The British relied on quinine, and while I love a good G&T, these days we have pills to fend off severe malarial infections. There are a lot of options on the market, but they all have pros and cons. Cost is a big factor for a lot of people. Daily vs weekly doses is another consideration. I’m not good at daily pills even short term, so weekly was a big appeal for me. Then there’s strain resistance. Malaria in some places has become resistant to the more commonly used drugs. That includes Senegal, for which Chloroquine is contra-indicated due to resistant strains of malaria that dominate here. That left me with Mefloquine which has a higher than desirable risk of psychological side effects, many of which are co-morbid with the psychological effects of culture shock, with the added bonus of vivid dreams, possible hallucinations, and seizures. Yay. Studies are fairly limited and there is no data which studies the effects of the medication in the subject’s home culture, so no way to know what amount of the distressing symptoms are a result of living in Africa as a foreigner or of the Mefloquine.

And I hate hate hate the idea that as women we are constantly judged as overemotional due to our hormones, but I did just turn 45 and some of this mood swing business could legitimately be a part of perimenopause. So we have at least 5 different factors in play: 1) pre-existing conditions, 2) environmental adversity, 3) culture shock, 4) medicine and 5) getting old. The chances of my mental/emotional state being only and entirely just ONE of these factors is 0, and 3 of them are directly related to living in Dakar.

Is It Real or Is It Culture Shock?

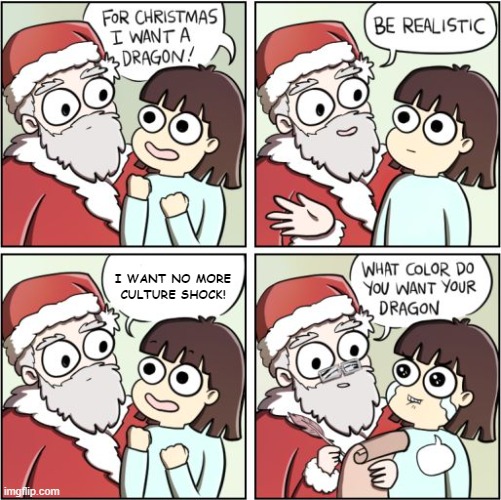

The time is coming where I have to start making decisions about my future. We’re already making plans for our mid-year conference, and before you know it, the 10 month Fellowship will be over. Whatever happens, I know that this is a life altering and immeasurably valuable and unique experience. I don’t regret the decision to come in any way. I just want my future self to be able to tell some “it was so awesome” stories about Senegal alongside my newfound stories of resilience and overcoming adversity. However, I’m having a really hard time making plans or looking forward to anything while I’m in this particular loop of the emotional rollercoaster. So please, Santa, all I want for Christmas is no more culture shock… or if that’s not possible, then I’ll take one in blue.

Pingback: They Say You Can Never Go Home | Gallivantrix