Glowworms are one of the most unique and beautiful secrets of wildlife in Aotearoa. Although various bio-luminescent insects exist throughout the world (I used to chase and catch fireflies in the New England area of the US when I was a child -releasing them after an hour or so of intense admiration), and however fascinating these glowing bugs are, there is nothing quite like the underground galaxies in the caves of New Zealand. My trip could not have been complete without a visit. As a bonus, I got to try my first black water rafting experience, too!

While I originally hoped to do the caves before the Hobbits, it turned out to be a good thing that my plans got swapped. Sunday had been beautiful and sunny as I wandered through Hobbiton, but I woke up Monday to a grey sky and light rain. Weather that would have put a damper (pun intended) on Hobbiton became wholly irrelevant to my enjoyment for the day since I would be spending it underground. Prior to my arrival in NZ, I had been under the impression that the glowworms only lived in caves, so I scheduled some time for myself to explore underground. My foray unsupervised into Waipu had been a wipe out, so to speak, but Waitomo offered plenty of guided tours that also included all the special caving equipment. As happy as I had been to learn that glowworms could also be seen in the bush, as magically fairy dusted as I was to have been able to find them not once, but twice above ground, I was still eager to see them in the caves where I was told their numbers were greatly increased, and where we would view them with no other light source but their own bio-luminescence.

There are several companies running a variety of tours in the caves at Waitomo, so feel free to shop around. I didn’t realize how many there were until I arrived at the hostel and saw the wall of brochures. Most of the companies don’t do a whole lot of online advertising, but if the options you find online don’t make you happy, rest assured there are more. The main types of tours are simple walking tours (no equipment needed), gentle boat tours (a group in a boat floating through the caves), adventurous caving/black water rafting (gear supplied, reasonable fitness required, clambering around and getting wet), and insanely adventurous caving (gear supplied, good fitness, zip-lines, fox-lines, rappelling, wall climbing, etc). Each of the companies offers some variety of these and everyone’s camera policy is different, so it’s just a matter of finding the one that fits you. I went with a winter sale that gave me one walking tour and one black water rafting tour. Ultimately, despite the fact that there were three caves to go through, I chose to to both tours in the same cave, Ruakuri.

Entering Ruakuri

I scheduled my walking tour first. I arrived at the tour center in time to get registered and check out what would be my lunch options later in the day. We didn’t need any special gear for the walking tour, so when the guide showed up, I just hopped in the van with her and we rode off to collect the other guests. (there are multiple pick up spots, too). We had a small group, just 6 of us including our guide, so it was a nice private feeling tour.

I scheduled my walking tour first. I arrived at the tour center in time to get registered and check out what would be my lunch options later in the day. We didn’t need any special gear for the walking tour, so when the guide showed up, I just hopped in the van with her and we rode off to collect the other guests. (there are multiple pick up spots, too). We had a small group, just 6 of us including our guide, so it was a nice private feeling tour.

Ruakuri means “two dogs” in Maori and as we stood in an entirely fake made-of-concrete cave entrance, our guide explained that the cave was so named because one day the local tribe spotted a pair of dogs in the mouth of the cave. Dogs were rare, as only the kuri that the migrating Maori had brought with them from Polynesia lived in NZ before the British came. Kuri were valued for fur and meat (not necessarily as companion animals the way we think of dogs today), and the fur was reserved for those with the highest standing. So it was that when this tribe found the dogs, they killed them and made their fur into a cloak for the chief. Whenever he would win a great battle, he would go to the cave and lay the cloak down on the ground in thanks. It became known as two-dog cave, or Ruakuri.

The reason we were standing in a concrete cave instead of a limestone one for this speech is that the Maori also believe that caves are entryways to the underworld and would often place the bodies of the dead in cave mouths to help their spirits on the way. The original British invaders didn’t really care, but since then the Kiwis have developed some cultural sensitivity (and laws) about Maori ancestral burial sites, and a new entrance had to be constructed. Given the context, I don’t mind in the least.

Once inside, we passed through a very James Bond Villain sort of airlock tunnel that was part of the system to help regulate air, temperature and moisture within the cave. We emerged at the top of a spiral of softly glowing lights. When the new entrance was built, the owners of the land decided that they wouldn’t just make do with a stairwell or switchback, and instead installed a rather stunning ramp that gently wraps around the wide cylindrical shaft, making Ruakuri the only wheelchair accessible cave in New Zealand (and several other countries, I’m sure). From the ceiling above us came a thin but constant stream of water, beating down upon a worn stone below. When we reached the bottom, we were offered the opportunity to use the stone basin where the falling water collected to wash our hands, a symbolic act I have encountered in Buddhist and Shinto temples that is also present in Maori beliefs that cleanses the impurities of the world from one before entering a sacred space.

Once inside, we passed through a very James Bond Villain sort of airlock tunnel that was part of the system to help regulate air, temperature and moisture within the cave. We emerged at the top of a spiral of softly glowing lights. When the new entrance was built, the owners of the land decided that they wouldn’t just make do with a stairwell or switchback, and instead installed a rather stunning ramp that gently wraps around the wide cylindrical shaft, making Ruakuri the only wheelchair accessible cave in New Zealand (and several other countries, I’m sure). From the ceiling above us came a thin but constant stream of water, beating down upon a worn stone below. When we reached the bottom, we were offered the opportunity to use the stone basin where the falling water collected to wash our hands, a symbolic act I have encountered in Buddhist and Shinto temples that is also present in Maori beliefs that cleanses the impurities of the world from one before entering a sacred space.

A Cave Walk

Once inside the cave, we were treated to chamber after chamber of beautiful limestone growths and formations. I’m lucky enough to have explored several of the best limestone caves in the US and I still found this one to be both beautiful and worthwhile. Like everything in NZ, the cave could not just be one type of landscape, but changed continuously as we traveled. In addition to the stunning stalagmites and stalactites, we saw curtain formations, several alternate types of mineral formations I don’t know all the names of because I’m not a geologist, some fossil seashells, some heavily layered rock, at least one natural chimney in addition to the man-made tube used to pipe in the concrete for the wheelchair safe pathways, and of course the glowworms. I should mention that anywhere a concrete path would have damaged formations, they instead used metal catwalks, sometimes bolstered from the floor, sometimes the walls, and at least once, suspended from the ceiling. They did everything possible to keep the cave intact while also making it accessible to everyone.

Once inside the cave, we were treated to chamber after chamber of beautiful limestone growths and formations. I’m lucky enough to have explored several of the best limestone caves in the US and I still found this one to be both beautiful and worthwhile. Like everything in NZ, the cave could not just be one type of landscape, but changed continuously as we traveled. In addition to the stunning stalagmites and stalactites, we saw curtain formations, several alternate types of mineral formations I don’t know all the names of because I’m not a geologist, some fossil seashells, some heavily layered rock, at least one natural chimney in addition to the man-made tube used to pipe in the concrete for the wheelchair safe pathways, and of course the glowworms. I should mention that anywhere a concrete path would have damaged formations, they instead used metal catwalks, sometimes bolstered from the floor, sometimes the walls, and at least once, suspended from the ceiling. They did everything possible to keep the cave intact while also making it accessible to everyone.

Seeing the glowworms up close in the cave was definitely a treat. Our guide shone her lamp askance onto a wall full of the little bugs, causing the feeding strings to become visible. Although I knew they must be there, when I was in the bush, I hadn’t wanted to shine a light directly onto the worms, and so didn’t really see the webs. But here, because of the shape of the wall, she was able to side-light the webs while still leaving most of the worms in darkness, meaning we could see both at the same time. My camera almost captures what that looked like, and certainly gives a clear view of the feeding lines. While only a few of the brightest bugs show up in the black portion of the photo here, to the naked eye, that space was covered in tiny blue dots of light.

Glowworms are larval insects who secure themselves to something dark and damp like the cave wall, then lower a strand of sticky silk. When some poor unsuspecting flying insect thinks their little glow is the moon and gets trapped in the web, the glowworm can then reel in the line and dine on the trapped flier’s brains. They are also quite territorial, so we were warned to be careful not to move the strands lest they become entangled with one another and cause a fight to the death to ensue between neighbors. It’s a little dichotomous to think of these beautiful serene lights as emanating from violent brain eaters, but then again, the fairies they are so often likened to are said to be beautiful yet cruel as well, so perhaps that metaphor is not so far off.

Glowworms are larval insects who secure themselves to something dark and damp like the cave wall, then lower a strand of sticky silk. When some poor unsuspecting flying insect thinks their little glow is the moon and gets trapped in the web, the glowworm can then reel in the line and dine on the trapped flier’s brains. They are also quite territorial, so we were warned to be careful not to move the strands lest they become entangled with one another and cause a fight to the death to ensue between neighbors. It’s a little dichotomous to think of these beautiful serene lights as emanating from violent brain eaters, but then again, the fairies they are so often likened to are said to be beautiful yet cruel as well, so perhaps that metaphor is not so far off.

The cave was nicely lit for the walking tour, and you can see the rest of my photos over on Facebook here.

Black Water Rafting

After lunch, I had my second cave trip planned for a higher level of adventure. Black water rafting is so named because in the cave there is no light, so the water is black. It’s not merely an underground version of whitewater rafting, which is done in multi-person boats down exciting rapids and involves lots of coordinated paddle maneuvering to avoid rocks and whirlpools. In caves the water does not flow so predictably in a space where we can be assured of having air all the time, and there is certainly not enough light to see obstacles far ahead. So black water rafting is instead a kind of wet spelunking with an inner-tube.

We started off by changing into some cave climbing wet-suits. These weren’t just regular SCUBA suits; they had special padding on the knees and bottom to help prevent injuries as we crawled and scooted around in the small tunnels. These suits were also 2 pieces, an overall style pants part and a long jacket. I am a short, round person and no neoprene suits were designed to my measurements even a little bit, so by the time I get something that fits my shoulders, bust and hips, its about 6 inches too long everywhere else, legs arms and torso (and rather unfortunately, it pushed up on my neck and chin so I had to unzip the first 5 inches of the jacket just to be able to breathe). In addition, the material is very stiff, so I felt like I was wearing a suit of armor built for someone 6 inches taller than me. I was suddenly very glad I’d decided on the less extreme version of the extreme adventuring.

We started off by changing into some cave climbing wet-suits. These weren’t just regular SCUBA suits; they had special padding on the knees and bottom to help prevent injuries as we crawled and scooted around in the small tunnels. These suits were also 2 pieces, an overall style pants part and a long jacket. I am a short, round person and no neoprene suits were designed to my measurements even a little bit, so by the time I get something that fits my shoulders, bust and hips, its about 6 inches too long everywhere else, legs arms and torso (and rather unfortunately, it pushed up on my neck and chin so I had to unzip the first 5 inches of the jacket just to be able to breathe). In addition, the material is very stiff, so I felt like I was wearing a suit of armor built for someone 6 inches taller than me. I was suddenly very glad I’d decided on the less extreme version of the extreme adventuring.

Training Time

Despite feeling like a sausage in a tin suit, I was excited for the journey and waddled along after the taller and more lithe members of the group toward the inner tubes for our training. There were 6 people (7 with guide) in this group, which was a good size. We learned how to use our helmet lights, and how to link together in an inner-tube chain so we wouldn’t loose each other in the dark float, and finally we learned how to jump off a waterfall backwards. Yep, backwards.

I had read in the description of this adventure that it would include 2 waterfall jumps. I’m not sure what I had in my head, there were pictures on the website of people in inner-tubes floating along, perhaps I though we would just go over that way, or jump feet first with the tubes around our waists, but the reality was much more ridiculous. We went to a short pier over a day-lit portion of the stream to learn the proper backwards waterfall jumping technique. It is this: stand firmly at the very edge of the jumping platform, hold your inner tube to your bottom and resist the urge to bend your waist or knees too much. Kick off and out from the platform into the empty space behind you, splash butt first into icy river water which then floods up your sinus cavity and trickles into parts of your wet suit that were previously warm.

Wet Spelunking

Once we finished our brief training, we headed over to a totally different entrance of Ruakuri than the walking tour had taken. Within the cave, the river was often not deep enough or wide enough for us to float on the inner tubes, so we spent a significant portion of the adventure carrying them or passing them around. However, the river was always underfoot which meant that walking involved keeping our balance in various intensities of rushing water and finding footing under water we could not see the bottom of (not because it was cloudy, but because of the lack of light and/or the white water foam). We often had to sit and scoot or sit and jump to get down steep ledges. Our guide knew the terrain well, however, and in difficult passages would tell us all exactly where to put which foot, knee, hand or elbow for the best way through.

Once we finished our brief training, we headed over to a totally different entrance of Ruakuri than the walking tour had taken. Within the cave, the river was often not deep enough or wide enough for us to float on the inner tubes, so we spent a significant portion of the adventure carrying them or passing them around. However, the river was always underfoot which meant that walking involved keeping our balance in various intensities of rushing water and finding footing under water we could not see the bottom of (not because it was cloudy, but because of the lack of light and/or the white water foam). We often had to sit and scoot or sit and jump to get down steep ledges. Our guide knew the terrain well, however, and in difficult passages would tell us all exactly where to put which foot, knee, hand or elbow for the best way through.

In one section of the cave, we were getting ready to enter a passage that required us to crawl hands and knees, but it was up from the main passage. The guide pointed to two divots in the rock and told us to put a right foot in one and the left knee in the other to get up. The step was about mid thigh height on me (another advantage you tall people have) which is something that is a little challenging but realistically achievable for me in “normal” clothes. However, at this point the overlong legs of my wet-suit became more than merely foolish looking because the stiff extra fabric was preventing me from lifting my leg high enough to reach the step! I felt like I was trying to lift my foot with a 40lb resistance band on my leg. I couldn’t even get my foot past mid-calf height and one of the other adventurers had to help by grabbing my foot and putting it up into the step. It was pretty embarrassing not to be able to do it for myself, but I was glad to be with people who so readily lent a hand. Once I got in the tunnel, I had the advantage over the taller folks, though, and I wiggled on through getting nice and warm in the process.

We came out back into the same chamber we had left our inner-tubes in. It turned out the crawling tunnel wasn’t strictly necessary but rather a fun part of the caving experience that we could do without loosing our floaties. After all, it’s not really caving if you haven’t had to wiggle through a tight fit, right?

Waterfall Jumping

We were scheduled to be underground for a little more than 2 hours, and quite a bit of that was spent making our way through the shallow but fast running water. When we came upon our first waterfall I hung back a little to try and get an idea of what the whole thing looked like. Our helmet lights weren’t very powerful (probably good so we didn’t blind one another) Even standing near the edge of the fall, I couldn’t get a sense of how far below the water was. When the first brave volunteer took the plunge, it became obvious it was only a short drop and was really no different from flopping down backwards onto a bean bag. Even knowing it was totally safe, knowing hundreds of people had done it before me and that the guide knew the space well enough to help me place my feet in just the right place, I still got some serious tummy butterflies. Unlike the pier, which is flat, dry and made of wood, we had to stand on an uneven rock ledge with water rushing past our feet… backwards. At one point my guide asked me to step a little closer to the edge to prepare for my jump and I think that tiny step was actually more nerve-wracking than the actual leap.

The water got less predictable and less shallow as we progressed. There was a churning whirlpool of doom that was called something like the concrete mixer or the meat grinder, but basically don’t fall in it because it will suck you under and batter you blue. The floor became more uneven so I would go from ankle deep water into knee deep water in one step. I spent a lot of time with one hand on the wall trying to keep my feet from being swept out from under me by the fast moving water, while my other hand held the light but cumbersome inner-tube. I had a blast. I’ve been caving in places that you had to bring your own light, the Ape Caves and Guler Ice Caves near Seattle were like that, but they were merely damp and required no special equipment beyond a light. I went spelunking ages ago with my father in a place that gave us overalls and had us rappelling down walls and wiggling through tiny tunnels. This was the first time I’d been able to do more than just look at an underground river and despite the nerves. It was a beautiful and rewarding climb.

A Galaxy of Glowworms

The true prize at the end of the tunnel were the two spots of deep slow water where we could lay in the tubes we’d dragged all this way and relax as we looked up at the cave roof. It’s a prize because here is where the glowworms live in large numbers, occupying much more space than any of the passages we had walked through up until then. For the first segment our guide had us link up, holding the shoes of the person behind us to form a chain, and then he grabbed on to my boots (I was in front at this point) and towed us all along behind him as he waded forward. We all turned our lights off to have the best possible view of the glowworms, which also means that while we were all going oooh aaah and floating along, our guide was pulling us along by memory in pitch blackness, so kudos to that guy.

The true prize at the end of the tunnel were the two spots of deep slow water where we could lay in the tubes we’d dragged all this way and relax as we looked up at the cave roof. It’s a prize because here is where the glowworms live in large numbers, occupying much more space than any of the passages we had walked through up until then. For the first segment our guide had us link up, holding the shoes of the person behind us to form a chain, and then he grabbed on to my boots (I was in front at this point) and towed us all along behind him as he waded forward. We all turned our lights off to have the best possible view of the glowworms, which also means that while we were all going oooh aaah and floating along, our guide was pulling us along by memory in pitch blackness, so kudos to that guy.

It’s hard to describe the actual sensation. It helps if you’re not claustrophobic, I suppose, but the cave is fairly open at this point. Once the lights go out you have the very unique physical sensation of floating, because you are, with almost no visual reference at all. The water is ice cold, but the suits were doing their job and I wasn’t cold. I was not alone because I had the reassuring grip of the guide’s hand on my toes and my own grip on the boots behind me. And all at once I had no butterflies at all. It was the safest most peaceful feeling floating in the blackness with these people hundreds of feet under the earth.

Then I look up and it is nearly as though I am outside staring up at a night sky free of light pollution. The ceiling is covered in tiny glowing blue lights. It doesn’t look like the photographs. Those photographs are low light exposure or even time lapse and they make the bugs look like LED lights or computer animations from Avatar. I don’t mean to suggest the reality is a let down at all, just that I can’t show you what it looks like in a photograph. When you see a sunset, or the starry sky, or the full moon at dusk and you know that there is no way any photograph will ever capture that moment, it’s like that. As I lay on my inner tube floating in complete blackness, my only cues of movement coming from my inner ear and the slowly shifting perspective of this underground galaxy above me. I realized soon that the bugs weren’t evenly distributed across the ceiling like stars, but rather following a path like the river itself, winding and bending, widening and narrowing as it led us forward.

The Total Ecosystem Experience

With no lights, no watch and no way to tell how long I had stared hypnotized by this phenomenon, I felt both like an eternity had passed and that it had passed too quickly. Soon it came time to turn our lights back on and navigate our way to the next goal. After a bit more climbing, wading and one more waterfall jump, we came to what our guide called the lazy river. The current was strong enough to keep us moving forward and this time we did not link our tubes to float, but set off as individuals. The sensation was different.

Firstly because I had to put my hands in the water from time to time to paddle, and since I had no inner tube behind mine, when I tilted my head back for the best view, my hair dunked into the water as well, giving me quite the chill, though not unpleasantly so. Also, as we were at the mercy of the currents, I often drifted into walls that I had to push off, while not pushing so hard as to throw myself into the opposing wall. This meant that I was more engaged with the cave itself than the first float, but I was also not engaged with the other people except when we bumped into one another. The experience was no less intense or amazing for that, but instead of feeling an almost outer space quality of the first float, I was tangibly aware of the water and the rock through my bare hands, connecting the river, the cave and the beautiful but carnivorous lights above me into one ecosystem.

Wrapping Up & Moving On

I probably could have lay and stared at that view forever, but too soon it was over and we headed to the exit. It was a good level of adventure, physically challenging enough to make me feel like I’d done something and to make me ok with only doing the 3 hour version, but not so grueling as to make me not able to enjoy the calm and peaceful portions. The backward jumping waterfalls were a new type of face your fears activity that really helped remind me of the joy of leaping into the unknown. And the slow floats under the gentle blue glow of the unique little bugs are an image I hope to treasure for many years to come.

When we got back to the base, we took a final victory picture, doing our best to imitate the Olympic rings for the Rio Olympics. Then we peeled off the wet suits and ran shivering in our bathing suits into the hot showers to warm up and clean off before getting into dry clothes. They also had some hot soup and toasted bagels for us in the cafe when we came in so we could replenish some calories and get warm from the inside too. Our guide did his best to take photos of us in the cave, but was by himself that day and often had his hands full helping one or more of us find the foothold or handhold we needed to get through. Nonetheless, they did show the photos of our group up on big TVs for us to see while we sipped our soup. Most of the pictures were of us outside the cave or in the cave mouth, so it’s not especially great at capturing the in cave experience visually. Hopefully I painted a picture with my words.

When we got back to the base, we took a final victory picture, doing our best to imitate the Olympic rings for the Rio Olympics. Then we peeled off the wet suits and ran shivering in our bathing suits into the hot showers to warm up and clean off before getting into dry clothes. They also had some hot soup and toasted bagels for us in the cafe when we came in so we could replenish some calories and get warm from the inside too. Our guide did his best to take photos of us in the cave, but was by himself that day and often had his hands full helping one or more of us find the foothold or handhold we needed to get through. Nonetheless, they did show the photos of our group up on big TVs for us to see while we sipped our soup. Most of the pictures were of us outside the cave or in the cave mouth, so it’s not especially great at capturing the in cave experience visually. Hopefully I painted a picture with my words.

I spent a long time lingering in the cafe and ended up chatting with two Chinese ladies returning from their own caving trip. We had a good talk about Buddhism and how to look for the teachers the universe sends us outside the temple as well as how to find and follow the path that’s set out for us in each life. This is something I give a lot of thought to, as I tend to spend more time in the world than in the temple. One of the girls said she hoped I could help more Westerners understand Buddhism better, which is a pretty lofty goal. When I found out they were going to Rotorua next, I gave them all my Google Map data for the hot springs there. I may not be destined to spread the Dharma to the West, but I can at least help a fellow traveler find some hidden treasures.

Waitomo was my last full day in the Land of the Long White Cloud. I drove back to Auckland that evening in preparation for departing the next day. It was hard to watch the rural roads return to urban highways, knowing that I would bid farewell to this land that had greeted me so warmly, but the stories aren’t quite over yet. There’s one more post coming after this one, filled with the odds and ends of smaller precious experiences that didn’t fit into any of the larger narratives so far. As always, thanks for reading and please check out my Facebook and Instagram for everyday updates in my travels! ❤

I remember having some picture books as a kid about Bilbo and Frodo Baggins. They were highly simplified versions of the stories in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, but my mother loved those stories so much, she made sure I got started early. The books had read along audio cassettes that I could play in my own little cassette player (because digitial music didn’t exist yet, that’s why). I learned about Golum and the One Ring while I was learning to read. It’s safe to say that the stories of Middle Earth are embeded in my foundation.

I remember having some picture books as a kid about Bilbo and Frodo Baggins. They were highly simplified versions of the stories in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, but my mother loved those stories so much, she made sure I got started early. The books had read along audio cassettes that I could play in my own little cassette player (because digitial music didn’t exist yet, that’s why). I learned about Golum and the One Ring while I was learning to read. It’s safe to say that the stories of Middle Earth are embeded in my foundation. In high school, we used to use Dwarven runes to write secret notes and one of my friends even learned basic Elvish. In 1999 or 2000, my mother and I were walking out of some movie or other and saw a poster on the wall of the theater with Elijiah Wood and my mother immediately exclaimed, “It’s Frodo!” without even reading the text on the poster. It was indeed Frodo, and the poster was the first advertisement for Peter Jackson’s film rendition of the epic stories. Now the books have spawned a movie franchise, sharing Tolkien’s work with a whole new group of fans with 6 movies so far, and I hear more in the works. So, when I found out that the Hobbiton movie set was still alive and well in New Zealand, I of course fantasized about going there. And, when I found my travels taking me down under this year, I finally got my chance.

In high school, we used to use Dwarven runes to write secret notes and one of my friends even learned basic Elvish. In 1999 or 2000, my mother and I were walking out of some movie or other and saw a poster on the wall of the theater with Elijiah Wood and my mother immediately exclaimed, “It’s Frodo!” without even reading the text on the poster. It was indeed Frodo, and the poster was the first advertisement for Peter Jackson’s film rendition of the epic stories. Now the books have spawned a movie franchise, sharing Tolkien’s work with a whole new group of fans with 6 movies so far, and I hear more in the works. So, when I found out that the Hobbiton movie set was still alive and well in New Zealand, I of course fantasized about going there. And, when I found my travels taking me down under this year, I finally got my chance. The tour is 2 hours long and starts at the visitors center where a massive car park surrounds a quaint gift shop and cafe. I was truly surprised at the number of cars in the lot when I arrived. The movie set is outside Matamata, and is quite remote. I had seen more sheep than people my whole drive over, and the nearest petrol station was more than 10 minutes away. When I turned into the car park, however, it was like a shopping mall on a Black Friday, I nearly didn’t find a parking spot. I did go on a Sunday, which may have accounted for the higher turn out, but there is no doubt that Hobbiton is a prime attraction. There is a fleet of green buses (the color of Bag End’s front door) emblazoned with the Hobbiton logo that drive visitors from the car park over to the movie set itself. On the way, the guide, Sam (our guide was named Sam, he swears it’s his real name and just a coincidence) told us that originally there had been no road into the farm this way. The New Zealand Army was contracted to come in and build the road so that all the set and filming equipment could be moved in. The farmer himself was under a non-disclosure agreement, so when one of his neighbors asked why the army was on his farm, all he could say was that they had been selected for a random road building exercise.

The tour is 2 hours long and starts at the visitors center where a massive car park surrounds a quaint gift shop and cafe. I was truly surprised at the number of cars in the lot when I arrived. The movie set is outside Matamata, and is quite remote. I had seen more sheep than people my whole drive over, and the nearest petrol station was more than 10 minutes away. When I turned into the car park, however, it was like a shopping mall on a Black Friday, I nearly didn’t find a parking spot. I did go on a Sunday, which may have accounted for the higher turn out, but there is no doubt that Hobbiton is a prime attraction. There is a fleet of green buses (the color of Bag End’s front door) emblazoned with the Hobbiton logo that drive visitors from the car park over to the movie set itself. On the way, the guide, Sam (our guide was named Sam, he swears it’s his real name and just a coincidence) told us that originally there had been no road into the farm this way. The New Zealand Army was contracted to come in and build the road so that all the set and filming equipment could be moved in. The farmer himself was under a non-disclosure agreement, so when one of his neighbors asked why the army was on his farm, all he could say was that they had been selected for a random road building exercise.

and even one with an open door to give us the chance to stand inside the traditional round portal. There is nothing inside, of course, the interior of the Hobbit holes were only filmed in the studio, but it makes for a unique and fun photo opportunity to place yourself in the role of a Hobbit. I didn’t have time on this trip, but when I get the chance to go back and stay in NZ longer, I’d love to dress up and get some photos in cosplay on this set. I’d also love to bring my niece and nephew before they get too big (Gnome, Squidgette, I’m talking to you) because so many of the Hobbit sized sets are perfect child size and include a lot of props that are not hidden behind gates. There was a Chinese family in our group and watching the little ones pose in front of the smallest Hobbit holes was a cuteness overload.

and even one with an open door to give us the chance to stand inside the traditional round portal. There is nothing inside, of course, the interior of the Hobbit holes were only filmed in the studio, but it makes for a unique and fun photo opportunity to place yourself in the role of a Hobbit. I didn’t have time on this trip, but when I get the chance to go back and stay in NZ longer, I’d love to dress up and get some photos in cosplay on this set. I’d also love to bring my niece and nephew before they get too big (Gnome, Squidgette, I’m talking to you) because so many of the Hobbit sized sets are perfect child size and include a lot of props that are not hidden behind gates. There was a Chinese family in our group and watching the little ones pose in front of the smallest Hobbit holes was a cuteness overload. Jackson’s attention to detail and commitment to the book was so intense that during the filming, he was unable to find plum trees in the right size to match a written description of Hobbit children sitting under plum trees, so instead he brought in pear and peach, but stripped them of their fruit and leaves to replace it with plum foliage, each leaf wired on by hand. The scene is only in the extended edition and only visible for about 2 seconds.

Jackson’s attention to detail and commitment to the book was so intense that during the filming, he was unable to find plum trees in the right size to match a written description of Hobbit children sitting under plum trees, so instead he brought in pear and peach, but stripped them of their fruit and leaves to replace it with plum foliage, each leaf wired on by hand. The scene is only in the extended edition and only visible for about 2 seconds.  Other examples of his eccentric dedication include the frog pond which had such an abundance of loud frogs that staff had to be employed to catch and move the frogs before filming

Other examples of his eccentric dedication include the frog pond which had such an abundance of loud frogs that staff had to be employed to catch and move the frogs before filming

It was very hard to leave behind the house on the the Hill, but our next stop was the party tree and the green field where Bilbo’s 111th birthday party was held. However magestic the party tree looked from afar, it was even more imposing up close. It wasn’t so big as Tane Mahuta, but it was taller and still an impressive girth. Unlike the oak tree, the party tree is a real and living tree that was one of the main reasons this piece of land was selected to be the Shire. Within the meadow, there were party decorations and Hobbit games for people to try out including a maypole, some stilts, a game of ring-toss and some see-saws. Children and adults alike had fun testing out the various activities and admiring the detail of the design.

It was very hard to leave behind the house on the the Hill, but our next stop was the party tree and the green field where Bilbo’s 111th birthday party was held. However magestic the party tree looked from afar, it was even more imposing up close. It wasn’t so big as Tane Mahuta, but it was taller and still an impressive girth. Unlike the oak tree, the party tree is a real and living tree that was one of the main reasons this piece of land was selected to be the Shire. Within the meadow, there were party decorations and Hobbit games for people to try out including a maypole, some stilts, a game of ring-toss and some see-saws. Children and adults alike had fun testing out the various activities and admiring the detail of the design.  Even the fence, which looked old and overgrown with lichen was artistically aged with plaster and paint, but indistinguishable even after we knew what to look for. Before we left the meadow, we stopped off at Samwise Gamgee’s own yellow round door where you could just imagine Rosy and the children playing in the garden.

Even the fence, which looked old and overgrown with lichen was artistically aged with plaster and paint, but indistinguishable even after we knew what to look for. Before we left the meadow, we stopped off at Samwise Gamgee’s own yellow round door where you could just imagine Rosy and the children playing in the garden.

There is something familiar yet otherworldly about the unique flora of New Zealand that must only seem familiar to the Kiwis themselves. For the rest of us, it is just different enough from what we are used to that it provides a sense of otherness, of the fantasitcal and created without being so foreign as to seem alien. The main context that I (and probably many of you) have become familiar with these plants unique qualities is in the films themselves, so it is no surprise that more than just the buildings here make me feel like I am walking in the footsteps of Bilbo himself.

There is something familiar yet otherworldly about the unique flora of New Zealand that must only seem familiar to the Kiwis themselves. For the rest of us, it is just different enough from what we are used to that it provides a sense of otherness, of the fantasitcal and created without being so foreign as to seem alien. The main context that I (and probably many of you) have become familiar with these plants unique qualities is in the films themselves, so it is no surprise that more than just the buildings here make me feel like I am walking in the footsteps of Bilbo himself.

There are comfy armchairs by the fire, and artwork all over the walls. You can have a taste of Hobbit food if you fancy a light snack (I tried the steak and ale pie, it was yummy), you can try on Hobbit clothes, wield Gandalf’s staff, and explore room after room reading the local Hobbit bulletin board, peeking at the range of knickknacks on shelves, visiting the Inn’s cat (not in the movies, but, you know, cats), or just admiring the large wooden carving that gives the Inn it’s namesake. I tried my best to multi-task, to take it all in, but I felt like I’d only begun to scratch the surface when Sam gathered us up to continue our trek.

There are comfy armchairs by the fire, and artwork all over the walls. You can have a taste of Hobbit food if you fancy a light snack (I tried the steak and ale pie, it was yummy), you can try on Hobbit clothes, wield Gandalf’s staff, and explore room after room reading the local Hobbit bulletin board, peeking at the range of knickknacks on shelves, visiting the Inn’s cat (not in the movies, but, you know, cats), or just admiring the large wooden carving that gives the Inn it’s namesake. I tried my best to multi-task, to take it all in, but I felt like I’d only begun to scratch the surface when Sam gathered us up to continue our trek.

the tattoos were done by cutting deep grooves in the skin and filling the wound with ink over and over so that it created a combination of ink and scar tissue for the design. Although the cheif joked that now they have a tattoo gun, he still pointed out that rarely do Maori get facial tattoos these days, and that the performers were all wearing make-up. Bear in mind the Maori tattoos may be the closest thing to a written language they developed and are just about as complex as any other ideographic language, so I’m only going to get the tip of the iceberg here.

the tattoos were done by cutting deep grooves in the skin and filling the wound with ink over and over so that it created a combination of ink and scar tissue for the design. Although the cheif joked that now they have a tattoo gun, he still pointed out that rarely do Maori get facial tattoos these days, and that the performers were all wearing make-up. Bear in mind the Maori tattoos may be the closest thing to a written language they developed and are just about as complex as any other ideographic language, so I’m only going to get the tip of the iceberg here. The basic legend: Mataora was a great chief who fell in love with and married a spirit from the underworld (Rarohenga) named Niwareka. One day Mataora struck her in a rage and she fled back to her father’s home in the underworld. Mataora felt remorse for his actions and decended to Rarohenga to find her. There he met her father instead who laughed at his painted face, wiping away the designs drawn there to show how useless they were. Mataora saw the permanent ta moka on his father-in-law’s face and asked him to mark his own face the same way. The pain was such that Mataora fell ill and his suffering softened Niwareka’s heart, so that when he recovered she agreed to return with him, and he promised never to hit her again as long as the markings on his face did not fade (so never). His father in law then granted him the knowledge of te moko and the Maori people have used it ever since.

The basic legend: Mataora was a great chief who fell in love with and married a spirit from the underworld (Rarohenga) named Niwareka. One day Mataora struck her in a rage and she fled back to her father’s home in the underworld. Mataora felt remorse for his actions and decended to Rarohenga to find her. There he met her father instead who laughed at his painted face, wiping away the designs drawn there to show how useless they were. Mataora saw the permanent ta moka on his father-in-law’s face and asked him to mark his own face the same way. The pain was such that Mataora fell ill and his suffering softened Niwareka’s heart, so that when he recovered she agreed to return with him, and he promised never to hit her again as long as the markings on his face did not fade (so never). His father in law then granted him the knowledge of te moko and the Maori people have used it ever since. These four birds are the bat (go with it), the parrot, the owl and the kiwi. The bat represents knowledge. The head of the bat rests in the center of the foread and the wings spread out to either side. The parrot is situated along the nose, particularly the beak on either sideof the nose. The parrot is a talkative bird and this represents oratory skills and is very important in an oral culture. The owl sits on the chin (the only facial tattoo typically available to women) and represents protection. Finally the kiwi, envision it’s long beak open, rests on the lower cheeks, meeting the chin moko in a fluid design. The kiwi represents stewardship of the earth.

These four birds are the bat (go with it), the parrot, the owl and the kiwi. The bat represents knowledge. The head of the bat rests in the center of the foread and the wings spread out to either side. The parrot is situated along the nose, particularly the beak on either sideof the nose. The parrot is a talkative bird and this represents oratory skills and is very important in an oral culture. The owl sits on the chin (the only facial tattoo typically available to women) and represents protection. Finally the kiwi, envision it’s long beak open, rests on the lower cheeks, meeting the chin moko in a fluid design. The kiwi represents stewardship of the earth. The only real hand to hand weapon is the club, or patu. The patu can be made from wood, bone or stone and resembles a paddle being narrow at the edges although not sharp enough to be a true bladed weapon. In addition to being carried to war like the long weapons, the patu were also used by women who remained at the village when the men were away hunting or fighting so that they could defend themselves against any hostile raiders. Women were expected to be skilled enough with the patu to kill their attackers. The chief pointed out that due to the shape of the patu, if one hit the skull of an enemy with the edge and twisted, it would pop the top of the head right off, handily combining village defense and dinner. Yes, the Maori used to be cannibals, too, but don’t worry, he told us “now we have McDonald’s”.

The only real hand to hand weapon is the club, or patu. The patu can be made from wood, bone or stone and resembles a paddle being narrow at the edges although not sharp enough to be a true bladed weapon. In addition to being carried to war like the long weapons, the patu were also used by women who remained at the village when the men were away hunting or fighting so that they could defend themselves against any hostile raiders. Women were expected to be skilled enough with the patu to kill their attackers. The chief pointed out that due to the shape of the patu, if one hit the skull of an enemy with the edge and twisted, it would pop the top of the head right off, handily combining village defense and dinner. Yes, the Maori used to be cannibals, too, but don’t worry, he told us “now we have McDonald’s”. Pavlova was a dessert that by it’s name made me assume it was from some Slavic country, but the natives at my table told me firmly it was invented in New Zealand, no matter what lies the Australians are spreading. The pavlova is named after a Russian ballerina, which explains why I thought it seemed linguistically Slavic. It’s like a merenge but more complicated, having a crispy exterior and fluffy interior. It’s also supposed to be very tricky to make and prone to collapse if it’s cooled too quickly. It’s traditionally served with whipped cream and fresh fruit. I found it unique and delightful.

Pavlova was a dessert that by it’s name made me assume it was from some Slavic country, but the natives at my table told me firmly it was invented in New Zealand, no matter what lies the Australians are spreading. The pavlova is named after a Russian ballerina, which explains why I thought it seemed linguistically Slavic. It’s like a merenge but more complicated, having a crispy exterior and fluffy interior. It’s also supposed to be very tricky to make and prone to collapse if it’s cooled too quickly. It’s traditionally served with whipped cream and fresh fruit. I found it unique and delightful. How are

How are  I had noticed during some of the talks that there were some unfamiliar gender roles being described. For example, the chief had to be male, and it was possible for a man to take more than one wife, but women were the landholders. Pre-colonial Maori gender roles appear to have been definitive, but not derisive. That is to say, women had very clear roles and responsibilities, but they were not thought of as lesser than men’s roles, nor were women seen as belonging to men. A woman did not take her husband’s name nor relinquish her membership to her own family or tribe at marriage. Women were seen as the progenitors of life, responsible for childrearing and the home. The main difference is that these roles were not seen as lesser to men’s roles.

I had noticed during some of the talks that there were some unfamiliar gender roles being described. For example, the chief had to be male, and it was possible for a man to take more than one wife, but women were the landholders. Pre-colonial Maori gender roles appear to have been definitive, but not derisive. That is to say, women had very clear roles and responsibilities, but they were not thought of as lesser than men’s roles, nor were women seen as belonging to men. A woman did not take her husband’s name nor relinquish her membership to her own family or tribe at marriage. Women were seen as the progenitors of life, responsible for childrearing and the home. The main difference is that these roles were not seen as lesser to men’s roles. The two main reasons modern Maori no longer wear traditional facial tattoos are the painful physical process and the social stigma. As I described earlier, the moko isn’t done with a needle, but by carving grooves into the skin and coloring the wound. This process is both painful and dangerous, and although could be replaced with a tattoo gun, there remains the second issue. Even as the moko mark them like each other, they also mark the Maori as separate and other from the British colonials. Due to years of colonial mistreatment and outdated ideas of “savages” that boil down to little more than racism, the presence of Maori tribal tattoos can still be cause for discrimination in modern day New Zealand.

The two main reasons modern Maori no longer wear traditional facial tattoos are the painful physical process and the social stigma. As I described earlier, the moko isn’t done with a needle, but by carving grooves into the skin and coloring the wound. This process is both painful and dangerous, and although could be replaced with a tattoo gun, there remains the second issue. Even as the moko mark them like each other, they also mark the Maori as separate and other from the British colonials. Due to years of colonial mistreatment and outdated ideas of “savages” that boil down to little more than racism, the presence of Maori tribal tattoos can still be cause for discrimination in modern day New Zealand. My guide said that he generally felt fine with other people getting Maori tattoos or wearing their art or jewelry as long as it was respected. These Maori tattoo artists won’t just put any old design you want on your skin, they will listen to your story and make something unique to you using the traditional Maori symbols and styles. So, while I suppose it is possible to print something off the internet and go to a non-Maori tattoo artist to replicate it, that doesn’t seem to be what’s going on in NZ and so it’s far less an issue of misappropriation and more a way of sharing and honoring. Later research revealed that the name for Maori style tattoos for non-Maori (Pakeha) is kirituhi and so most Maori don’t even see the kirituhi as being the same as the moko (even if it appears similar in design) because it lacks the spiritual and familial connections of a true ta moko.

My guide said that he generally felt fine with other people getting Maori tattoos or wearing their art or jewelry as long as it was respected. These Maori tattoo artists won’t just put any old design you want on your skin, they will listen to your story and make something unique to you using the traditional Maori symbols and styles. So, while I suppose it is possible to print something off the internet and go to a non-Maori tattoo artist to replicate it, that doesn’t seem to be what’s going on in NZ and so it’s far less an issue of misappropriation and more a way of sharing and honoring. Later research revealed that the name for Maori style tattoos for non-Maori (Pakeha) is kirituhi and so most Maori don’t even see the kirituhi as being the same as the moko (even if it appears similar in design) because it lacks the spiritual and familial connections of a true ta moko. Before beginning the glowworm hunt, we passed by an outdoor village replica so that we could get a better look at the housing construction and village arrangement. This picture is in daylight, but when I was there it was night. It was a little hard to see in the dark, but the guide gave a good description of the house (as a body) and of the general village construction on a hillside that allowed for greater protection. Before we moved on, he reminded everyone not to shine the lights on the glowworms and also, to cup the lights in our hands and point them only at the ground, so we could see where we were walking without obstructing the night view. I think about 5% of the group listened to this, because most people were busily shining their lights all over the woods.

Before beginning the glowworm hunt, we passed by an outdoor village replica so that we could get a better look at the housing construction and village arrangement. This picture is in daylight, but when I was there it was night. It was a little hard to see in the dark, but the guide gave a good description of the house (as a body) and of the general village construction on a hillside that allowed for greater protection. Before we moved on, he reminded everyone not to shine the lights on the glowworms and also, to cup the lights in our hands and point them only at the ground, so we could see where we were walking without obstructing the night view. I think about 5% of the group listened to this, because most people were busily shining their lights all over the woods. They were a tribe of supernatural beings that lived deep in the forest, ate their food raw and shunned the light. They were described as having pale skin and red hair, and it is thought that the red-haired Maori are descendants of a union between Patupaiarehe and Maori women. The gloworms are sometimes said to be they eyes of the Patupaiarehe, since they can be seen only in the dark places. They were not spread evenly around New Zealand, but seem to be concentrated in certain areas including Rotorua where they are rumored to have come down from the mountains to drink from the pure waters of this spring. The spring puts out more than 24 million litres of water each day. The dark spots in the photos at the bottom of the pool are not rocks, it is the constant billowing of the seditment as it is churned by ever arising spring water from the bottom.

They were a tribe of supernatural beings that lived deep in the forest, ate their food raw and shunned the light. They were described as having pale skin and red hair, and it is thought that the red-haired Maori are descendants of a union between Patupaiarehe and Maori women. The gloworms are sometimes said to be they eyes of the Patupaiarehe, since they can be seen only in the dark places. They were not spread evenly around New Zealand, but seem to be concentrated in certain areas including Rotorua where they are rumored to have come down from the mountains to drink from the pure waters of this spring. The spring puts out more than 24 million litres of water each day. The dark spots in the photos at the bottom of the pool are not rocks, it is the constant billowing of the seditment as it is churned by ever arising spring water from the bottom. we saw one of the native fish swimming around, but after the light was turned off and people started moving on, the freshwater eel resident of the spring came out. The second guide who was bringing up the rear tried to turn the light back on so I could see it better, but the light sadly drove it back into the rocks. However, having realized that I was more interested in the land than the majority of the tourists who were rushing ahead to get back to the halls, he stayed a little behind with me and started pointing out various interesting things around the bush.

we saw one of the native fish swimming around, but after the light was turned off and people started moving on, the freshwater eel resident of the spring came out. The second guide who was bringing up the rear tried to turn the light back on so I could see it better, but the light sadly drove it back into the rocks. However, having realized that I was more interested in the land than the majority of the tourists who were rushing ahead to get back to the halls, he stayed a little behind with me and started pointing out various interesting things around the bush. He told me about a kind of mud-skipper fish they have, and about some of the extinct land birds. He left his flashlight off and we found many more glowworms. I tried to show some of the other tourists on the walk, but they were too busy chatting to stop and look. The Mitai tribe has been watering their forest areas in order to boost the glow worm population. They aren’t seen above ground in great numbers because the atmosphere is often too dry, but a hydration program was having a profound effect on the local population and I saw probably hundreds throughout the walk all along the rock-sides sheltered by roots and leaves.

He told me about a kind of mud-skipper fish they have, and about some of the extinct land birds. He left his flashlight off and we found many more glowworms. I tried to show some of the other tourists on the walk, but they were too busy chatting to stop and look. The Mitai tribe has been watering their forest areas in order to boost the glow worm population. They aren’t seen above ground in great numbers because the atmosphere is often too dry, but a hydration program was having a profound effect on the local population and I saw probably hundreds throughout the walk all along the rock-sides sheltered by roots and leaves.

You can’t go anywhere in the US without being on some tribe’s ancestral land, though. I learned about the tribes as we moved around the country. I learned their words in each new place because white settlers used the names the Natives gave to things long after the people were relegated to reservations, forced to wear western clothes, speak English and go to church. And in the few places where they are reclaiming their place, they are still only known for 2 things: casinos and tourist attractions. Casinos because crazy sovereign land rights make gambling legal on reservations. These buildings are decked out in the tackiest stereotypes of Native imagery with wooden carved Indians in giant feather headdresses adorning the entryways and sacred patterns hanging on the walls, using the images of their culture to draw in suckers. Only slightly less crass are the informational tourism spots where descendants of colonialists can come and see an authentic teepee or wigwam or rain dance. Sometimes they even sell sweat lodge experiences. And as much as I want to learn about the people and the culture, because that is maybe my greatest passion in this life, it feels cheap and tawdry whenever I see these displays outside of museums. This is not to say they shouldn’t live their own culture, but there is a difference between living your lifestyle and putting on a show.

You can’t go anywhere in the US without being on some tribe’s ancestral land, though. I learned about the tribes as we moved around the country. I learned their words in each new place because white settlers used the names the Natives gave to things long after the people were relegated to reservations, forced to wear western clothes, speak English and go to church. And in the few places where they are reclaiming their place, they are still only known for 2 things: casinos and tourist attractions. Casinos because crazy sovereign land rights make gambling legal on reservations. These buildings are decked out in the tackiest stereotypes of Native imagery with wooden carved Indians in giant feather headdresses adorning the entryways and sacred patterns hanging on the walls, using the images of their culture to draw in suckers. Only slightly less crass are the informational tourism spots where descendants of colonialists can come and see an authentic teepee or wigwam or rain dance. Sometimes they even sell sweat lodge experiences. And as much as I want to learn about the people and the culture, because that is maybe my greatest passion in this life, it feels cheap and tawdry whenever I see these displays outside of museums. This is not to say they shouldn’t live their own culture, but there is a difference between living your lifestyle and putting on a show. Maori Colonization: The explorer Kupe took a really big boat and ventured across the ocean, leaving his home in search of new land. It’s believed that colonization of NZ from Polynesia was deliberate and slow after this. It took several hundred years of ocean faring boats going back and forth bringing more and more Maori. In fact, the seven main tribes now identify by which boat (waka) their ancestors arrived on. For those who have been wondering about why I keep using other names to refer to NZ, Kupe named the land Aotearoa which roughly translates to “land of the long white cloud”. There are a few legends on why, but no consensus. The seven waka hourua (ocean going boats) and later the seven tribes, are called Tainui, Te Arawa, Matatua, Kurahaupo, Tokomaru, Aotea and Takitimu.

Maori Colonization: The explorer Kupe took a really big boat and ventured across the ocean, leaving his home in search of new land. It’s believed that colonization of NZ from Polynesia was deliberate and slow after this. It took several hundred years of ocean faring boats going back and forth bringing more and more Maori. In fact, the seven main tribes now identify by which boat (waka) their ancestors arrived on. For those who have been wondering about why I keep using other names to refer to NZ, Kupe named the land Aotearoa which roughly translates to “land of the long white cloud”. There are a few legends on why, but no consensus. The seven waka hourua (ocean going boats) and later the seven tribes, are called Tainui, Te Arawa, Matatua, Kurahaupo, Tokomaru, Aotea and Takitimu. The Treaty of Waitangi was basically an agreement the Maori signed with the British crown stating that New Zealand was under British sovereignty, but that the Chiefs and tribes would keep their own land (selling only to British settlers, no filthy French or Dutch here, please), and that the Maori would have

The Treaty of Waitangi was basically an agreement the Maori signed with the British crown stating that New Zealand was under British sovereignty, but that the Chiefs and tribes would keep their own land (selling only to British settlers, no filthy French or Dutch here, please), and that the Maori would have  Modern Maori: Are there arguments about land rights, water rights, fishing and hunting rights… and every other aspect of sovereignty? Of course, but it’s much more like an argument between people of (nearly) equal footing than in the US where we’re still ignoring the fact that our reservations don’t have safe drinking water or can’t fish their own streams/

Modern Maori: Are there arguments about land rights, water rights, fishing and hunting rights… and every other aspect of sovereignty? Of course, but it’s much more like an argument between people of (nearly) equal footing than in the US where we’re still ignoring the fact that our reservations don’t have safe drinking water or can’t fish their own streams/  Armed with a better understanding of the history and a strong desire to learn more, I booked myself a table at the

Armed with a better understanding of the history and a strong desire to learn more, I booked myself a table at the  We were greeted at the entrance by a woman in traditional dress and (makeup) tattoo with the Maori greeting “Kia Ora” (

We were greeted at the entrance by a woman in traditional dress and (makeup) tattoo with the Maori greeting “Kia Ora” ( Next we broke into smaller groups and bundled outside to see some of the village. Our group first visited the boat displayed by the front gate. Our guide explained to us about the word “waka” (boat) and the three most common types of waka for daily use (fishing and transporting goods), for war, and for long ocean journeys. She pointed out to us the way in which this particular waka was made using planks and that was how we could tell it was a replica and not a traditionally made waka. In fact it was the prop from the movie

Next we broke into smaller groups and bundled outside to see some of the village. Our group first visited the boat displayed by the front gate. Our guide explained to us about the word “waka” (boat) and the three most common types of waka for daily use (fishing and transporting goods), for war, and for long ocean journeys. She pointed out to us the way in which this particular waka was made using planks and that was how we could tell it was a replica and not a traditionally made waka. In fact it was the prop from the movie

He taught them how to make the traditional war face which involves opening one’s eyes as wide as possible, sticking out the tongue toward the chin and doing an aggressive war cry. One of the men took this task quite seriously, doing his best to make an intimidating face and sound as he was shown, buy the other (and younger) was too cool for school and sadly sought audience attention by laughing at the process and doing a poor imitation of the war face, perhaps unwilling to look foolish, but in the end failing. We were asked to vote by applause and the man who went all out won by a landslide, which was nice, because I felt like he would at least take his duties as our chief for the night seriously and not treat it like some kind of opportunity for laughs.

He taught them how to make the traditional war face which involves opening one’s eyes as wide as possible, sticking out the tongue toward the chin and doing an aggressive war cry. One of the men took this task quite seriously, doing his best to make an intimidating face and sound as he was shown, buy the other (and younger) was too cool for school and sadly sought audience attention by laughing at the process and doing a poor imitation of the war face, perhaps unwilling to look foolish, but in the end failing. We were asked to vote by applause and the man who went all out won by a landslide, which was nice, because I felt like he would at least take his duties as our chief for the night seriously and not treat it like some kind of opportunity for laughs.

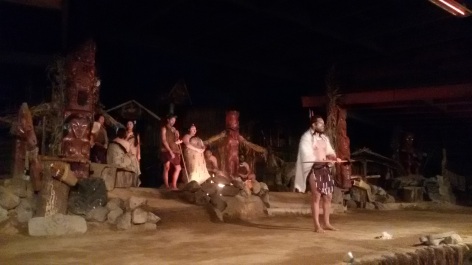

After the outdoor display, we headed into the performance hall. It was somewhere during this time that I started getting flashbacks to my childhood wild west/cowboys and Indians shows. The stage was set up to look like a Maori village, and once again, the guide was quite clear that it was a set and not real. The performance started with singing and dancing, then the cheif came out and gave a speech in Maori that of course none of us understood. While all the Maori performers were wearing traditional costumes, it struck me at once how different the cheif’s clothing was, especially the white fur cloak he wore. New Zealand has only one native land mammal, which is the bat, so where did this fur come from? It turns out that the Maori brought dogs, kuri, with them from Polynesia. The dogs were rare and their fur was prized as one of the elite materials for chieftain cloaks (along with fur seal skin), and because white was a common kuri coloring, I expect this was meant to represent a white kuri skin cloak and was quite prestigious indeed.

After the outdoor display, we headed into the performance hall. It was somewhere during this time that I started getting flashbacks to my childhood wild west/cowboys and Indians shows. The stage was set up to look like a Maori village, and once again, the guide was quite clear that it was a set and not real. The performance started with singing and dancing, then the cheif came out and gave a speech in Maori that of course none of us understood. While all the Maori performers were wearing traditional costumes, it struck me at once how different the cheif’s clothing was, especially the white fur cloak he wore. New Zealand has only one native land mammal, which is the bat, so where did this fur come from? It turns out that the Maori brought dogs, kuri, with them from Polynesia. The dogs were rare and their fur was prized as one of the elite materials for chieftain cloaks (along with fur seal skin), and because white was a common kuri coloring, I expect this was meant to represent a white kuri skin cloak and was quite prestigious indeed.  After the sung entrance and the chief’s introductions, they introduced traditional Maori instruments of which there are two main kinds: melodic and percussive. Melodic instruments (rangi) include flutes made from wood or bone, gourd instruments that are blown into or filled with seeds and shaken, and trumpet instruments made from shells. These are considered the domain of the Sky Father but each group and specific instrument has it’s own god/goddess or spirit associated with it. Percussive instruments (drums, sticks, poi -the white flaxen balls on strings, and a type of disc on a cord) are considered the heartbeat of the Earth Mother.

After the sung entrance and the chief’s introductions, they introduced traditional Maori instruments of which there are two main kinds: melodic and percussive. Melodic instruments (rangi) include flutes made from wood or bone, gourd instruments that are blown into or filled with seeds and shaken, and trumpet instruments made from shells. These are considered the domain of the Sky Father but each group and specific instrument has it’s own god/goddess or spirit associated with it. Percussive instruments (drums, sticks, poi -the white flaxen balls on strings, and a type of disc on a cord) are considered the heartbeat of the Earth Mother.

There are signs at every natural hot spring that basically warn you of 2 things:getting burned and getting sick. Because these are natural springs, the temperatures are not regulated, and water that is hot enough to burn you sometimes rises up from the ground in the river and pool beds. You can be sitting in lovely water and suddenly a hotter current will come by. You can take a step to the left and land on a patch of mud that is scalding hot. However, these are not insurmountable problems if you exercise a little caution and common sense. Don’t dig down into the mud/sand at the bottom. It’s hotter below the surface. Feel before you put your weight down, test the bottom gently with a hand or toe before you put your weight down so you can move away quickly if it’s too hot. If you’re really worried about it, you can always wear water shoes. The other thing to bear in mind is that hot water breeds microbes. In the case of the Rotorua springs, there is a small concern of amoebic meningitis. That sounds scary, but it can’t infect you through your skin, only if it gets up your nose, so just keep your head out of the water and you’re in the clear. If all this sounds like too much work, that’s why the spas exist.

There are signs at every natural hot spring that basically warn you of 2 things:getting burned and getting sick. Because these are natural springs, the temperatures are not regulated, and water that is hot enough to burn you sometimes rises up from the ground in the river and pool beds. You can be sitting in lovely water and suddenly a hotter current will come by. You can take a step to the left and land on a patch of mud that is scalding hot. However, these are not insurmountable problems if you exercise a little caution and common sense. Don’t dig down into the mud/sand at the bottom. It’s hotter below the surface. Feel before you put your weight down, test the bottom gently with a hand or toe before you put your weight down so you can move away quickly if it’s too hot. If you’re really worried about it, you can always wear water shoes. The other thing to bear in mind is that hot water breeds microbes. In the case of the Rotorua springs, there is a small concern of amoebic meningitis. That sounds scary, but it can’t infect you through your skin, only if it gets up your nose, so just keep your head out of the water and you’re in the clear. If all this sounds like too much work, that’s why the spas exist.

There’s a beautiful and fairly large waterfall there and a pool that’s deep enough to sit in and have the water come up to a comfortable chest level. This spot is

There’s a beautiful and fairly large waterfall there and a pool that’s deep enough to sit in and have the water come up to a comfortable chest level. This spot is

Not wanting to find my car locked up in the visitor’s spot, I

Not wanting to find my car locked up in the visitor’s spot, I  The first thing you see is the top of the falls. These are quite lovely and worth a gander, but the water up here is too shallow to enjoy a soak, so head on down the trail a little further and you’ll find the pool. Despite it’s lack of popularity, it was indeed marked with another Dept of Conservation sign warning us about mud burns and amoebic meningitis, so the government was clearly aware of the fact that people were coming here and was just as clearly not prohibiting it. Ostensibly, this is a result of the Queen’s Chain policy of reserving 20m of land around bodies of water (and prohibiting the private ownership of said water).

The first thing you see is the top of the falls. These are quite lovely and worth a gander, but the water up here is too shallow to enjoy a soak, so head on down the trail a little further and you’ll find the pool. Despite it’s lack of popularity, it was indeed marked with another Dept of Conservation sign warning us about mud burns and amoebic meningitis, so the government was clearly aware of the fact that people were coming here and was just as clearly not prohibiting it. Ostensibly, this is a result of the Queen’s Chain policy of reserving 20m of land around bodies of water (and prohibiting the private ownership of said water).

Back to New Zealand. It’s like time travel, or at very least like one of those novels that writes chapters from all different perspectives or storylines. You can see my trail through the north island here, starting in Auckland and then looping around Northland before swinging wide to the East and Coromandel Peninsula. Also, I’m afraid that the night-time stories don’t have accompanying pictures as I have not yet acquired a camera that actually shoots well in the dark. Think of it as imagination exercise.

Back to New Zealand. It’s like time travel, or at very least like one of those novels that writes chapters from all different perspectives or storylines. You can see my trail through the north island here, starting in Auckland and then looping around Northland before swinging wide to the East and Coromandel Peninsula. Also, I’m afraid that the night-time stories don’t have accompanying pictures as I have not yet acquired a camera that actually shoots well in the dark. Think of it as imagination exercise. My breakfast spot was nearby a public restroom and shower as well as a totally different path down to the water. When the hours lengthened enough to head to the beach, I wandered over to the changing rooms and got kitted out with my suit, sunscreen and shade hat. The clear sky of the night before had carried over into the morning and I didn’t want to get sunburnt while soaking up my hot spring. The beach was also quite full of people. I was even more glad in that moment that I’d had the chance to spend a few hours the night before in silence and solitude. I love people and I had a great time chatting with the other bathers that morning, but I am grateful it was not my only experience of the beach.

My breakfast spot was nearby a public restroom and shower as well as a totally different path down to the water. When the hours lengthened enough to head to the beach, I wandered over to the changing rooms and got kitted out with my suit, sunscreen and shade hat. The clear sky of the night before had carried over into the morning and I didn’t want to get sunburnt while soaking up my hot spring. The beach was also quite full of people. I was even more glad in that moment that I’d had the chance to spend a few hours the night before in silence and solitude. I love people and I had a great time chatting with the other bathers that morning, but I am grateful it was not my only experience of the beach.

Although Cathedral Cove car park is a mere 10 minutes up the road from Hot Water Beach, there is a further 45 minute hike (according to the sign) to the cove itself. The cove is not accessible except by taking this walk or by kayaking in from another point. It is famous more for it’s breathtaking beauty than for any particular historical importance, although it was used in the filming of